I will start and conclude this page with a quote from a good friend Alex Floyd. As a prominent botanist Alex Floyd always took the time to help anyone interested in plants. This was said to Tony Packer and myself one day at the Coffs Harbour Herbarium “It matters not how you pronounce the plant’s name, as long as we both persons know which plant we are talking about and we enjoy our association together with the plant.” We did.

I will start with the morphology of plants with drawings, while at the bottom I have indevoured to keep it simple and describe how the letters of the alphabet are said using Ancient Greek though to modern Latin. In fact it is a lot easier than you think. Good speaking.

“Where there is beauty, peace & tranquillity

You’ll find a plant blooming” – andi Mellis

Acacia ruppi [a-kay-sha, ru-pahy]

From Akazo which is Ancient Greek for to sharpener or a point.

From Rupp which is named in honour of Herman Montague Rucker Rupp; 1872-1956, who was an Australian born clergyman and botanist from Melbourne.

Over 19,000 Ancient Greek and Latin botanical names associated with Australian flora have been described with their original meanings, illustrations & reference to why the name was chosen where known.

“Love is a flower

You have to let it grow outwards from within

You cannot force love

You cannot buy love

It needs nurturing

It needs two or more

It needs trust

Like its environment it needs us

As much as we need it.” – andi Mellis

Boronia rosmarinifolia

[bor-oh-ni-a, rohz-mar-in-a–foh-li-a]

From Boronia which is named in honour of Francoise Borone.

From Rosemary which is Ancient Greek for the exotic herb rosemary and Folium, which is Latin for foliage. It refers to the leaves being similar to that of the Mediterranean Rosemary shrub.

“The beauty of a flower is only seen & appreciated by those who take the time to look at it closely.” – andi Mellis

Chloanthes parviflora [kloh-an-th-us, par-vi-flor-a]

From Chloa which is Ancient Greek for grass and Antha/Anthos which is Ancient Greek for the male reproductive parts of a flower or the flower. It refers to flowers, which have pilose hairs that resemble a field of grass surrounding the anthers. From Paûros which is Ancient Greek or later Parvum which is Latin for small & Fl?ris which is Latin for a flower or Fl?s which is the Roman Goddess of spring and flowers.

Author andi Mellis by Peng Mitre Chong Qing

Most of us have problems with Botanical names. Scientist to Gardeners all struggled, until this new approach came along. This botanary adds another dimension to botany for botanists and gardeners alike. It is a lot easier and much more fun when you know the meaning and origin of the word involved.

My early years in the nursery were bewildering with words like Cupaniopsis anacharioides. Then, as I was writing “The Bible of Botany”, I realized many keen gardeners and botanists all craved for the meaning of the plants name in simple everyday Aussie Lingo. Not a complex scientific glossary but an enjoyable, colourful and easy process of being aquainted with Latin or as with most plant names Ancient Greek in everyday use.

Before you delve deeper, it is important to understand that most of the descriptive language as well as the names of plants use Greek, Greek-Latin or at times pure Romanized Latin.

Why use Latin? The answer is simple, scientists use a universal language that is understood by botanists from every country all over the world. A plant that is pan tropical for example may be found in every country along the equator. It would have a different local name in every country and even by different groups of people in a single country. Latin is the standard World language even if it utilizes many Ancient Greek words.

Roman lower case is used in the alphabetical writing. In the case of a “box” it may be from the Ancient Greek theke or later from the Latin theca. The Roman upper case is used for the names of plant groupings above the species level. ie.- Plantia – Angiosperma- Eudicots- Rosids- Fabales- Fabaceae- Mimosoideae- Acacieae- Acacia- floribunda. Only the specie name subspecie, variety or type use all lower case.Why is there a preference for Greek Botanical names and terms instead of Latin, as is the case of many of the other sciences? The answer lays in the father of Botany or as some sources state “The Grandfather of Botany” the great Greek, Theophrastus (Tyrtamus ????????, Theophrastus ?????????? 370–c.286 B.C). [thee-o-fras-kus, thee-u-fras-tus] He wrote “Enquiry into Plants” & “The Causes of Plants”. Theophrastus wrote in depth detailing around 500 varieties of plants, which included Daucus the Carrot, Narcissus the Daffodil and Asparagus. An amazing result when you consider he did not have a computer and everything was hand written. Carl Linnaeus adopted the use of the names he applied to the plants he studied some 2000 years later such is the respect he has in the modern science of botany.

It is believed that he was educated in Philosophy in Lesbos by Alcippus. Later he moved to Athens, where he probably studied under Plato. It is understood that he became friends with Aristotle and joined Aristotle in their self-imposed exile from Athens. It was on Lesbos that Aristotle and Theophrastus began their research into natural science. Aristotle ventured into the science of zoology , while Theophrastus took to studying botany.

Theophrastus travelled widely throughout Greece to acquire plants. Later Alexander the Great collected and gave accounts of many plant distributions and habitats like cotton, banyan, pepper, cinnamon, myrrh and frankincense to Theophrastus as a result of his personal instructions.

The Southern and Central American family of Theophrastaceae includes the genus Clavija. The previously circumscribed family was much larger and consisted of seven genera and 95 species of trees and shrubs.

Theophrastus displayed a strong empathy not just for the science of plants, he noted in accurate detail their soils, weather and habitats but also the botanic garden he developed. He apparently left detailed instructions on the maintenance of his garden and where he wanted to be laid on his death. – Amongst his beloved plants.

GLOSSARY

Before you delve deeper into the glossary, it is important to understand that most of the glossary and descriptive language as well as the names of plants use Ancient Greek, Greek-Latin and pure Romanized Latin as mentioned above. It utilizes the Roman characters and is adopted in every language throughout the world as the standard communication.

While he named plants by type whether they be a tree, a shrub, an under shrub, a perennial or an annual may be simplistic today but 2,400 years ago it was a great step forward in understanding the workings of plants and how they interacted with each other in their environments. His greatest achievement that lives on to this day; in nomenclature, is the work he did with identifying the position of the ovaries within the flower. The position of the ovary; inferior or superior which is the basis of botanical identification to this day, followed by the pistil, stamens, petals, sepals, bracts, leaves and hairs etc. Amazingly this was the basis before DNA and is still the starting point of nomenclature to this day.

Theophrastus noted the importance of climate and soil types to the health of plants and the consequential relationship of health in humans. Again a science that is today in its renaissance through the organic movement, wellbeing and medical institutions.

Theophrastus noted the following differences when classifying plants:

- Differences between organs (external) and tissues (internal– grasses and reeds).

- Distinction of different types of tissues.

- Classification of plants into trees, shrubs, subshrubs and herbs.

- Distinction of flowering plants and nonflowering plants.

- Recognition of various types of sexual and nonsexual reproduction.

- Basic understanding of gross anatomy (CA and CO are modified leaves)

- Recognition of fruit in its modern technical sense and their anatomy. (pericarp etc.)

Theophrastus was opposed to eating meat on the grounds that it robbed animals of life and was therefore unjust. “Non human animals, he said, “can reason, sense, and feel pain and pleasure just as human beings do and what other animal species befriends another, just to kill it?”

Theophrasus’s own garden was the first Botanical Garden in history and was designed and created by him. He and his fellow students had a closer empathy with plants and could study them; daily, without the rigors of tracking tens or even thousands of kilometers into the countryside. This one great fete alone has been emulated in most countries of the world since. Australia has over 140 Botanic gardens and not one pays tribute to their father and founder. Sad very sad.

To conclude I note through some of Theophrastus’ sayings and works that they feature him to be a virtuous man of high morals and great wisdom. Below are some of his sayings that we should reflect upon daily. Doing this, enhances the meaning of life and gives life meaning.

“vitamregritfortuna??sapientia” (Life is ruled by fortune, not wisdom). This unfortunately still remains true to this day in a world of greed and misunderstanding; by the fortunate, of the role and importance of the individual and society in making their wealth and their repressing of the unfortunate. Being born with a silver spoon.

“? ??? ????? ?????? ??? ???? ?????, ?? ????????? ???? ???? ????????? ?? ?????” – “I zoí eínai chaméni gia tous néous , tha pethánoume móno ótan archízoume na zoúme” (“Life is wasted on the young, we die just when we are beginning to live.”) Only the elderly can truly appreciate what he said and the beauty of these words.

“Time is the most valuable thing we can spend. Giving it to a friend is the most valuable gift you can give.” While I have many friends; only a few can be classified as true friends, where time together is paramount to our friendship.

“An orator without judgment is akin to a horse without a bridle, “This led to Carl Linnaeus later quoting “An economist without the knowledge of botany is like a physicist without the knowledge of mathematics.” What an exquisite quote, which exhibits advanced knowledge that is again only understood by an elite few who have the capability to fathom the profound meaning and its implications in a modern world where the environment is displaced in the name of economics. He obviously visualized the ultimate destruction man was to inflict on the planet, nature and himself.

“We must consider the distinctive characters and the general nature of plants from the point of view of their morphology, their behavior under external conditions, their mode of regeneration, and the synergistic course of their life.”

“One may define flattery as a base companionship which is most advantageous to the flatterer,”

“The man of petty ambition if invited to dinner will be eager to be sat next his host.”

Note: Many words that are listed below in this glossary can be found under the plants name in the book. For example Adenthena is found under Adenthena is listed slightly different.

Adenthena: Aden is a Greek/Latin prefix pertaining to the presence of glands or a gland. Anthena is Ancient Greek for an Antha/Anthos which is Ancient Greek for the male reproductive part of the flower and later in roman and Latin as the flower. It refers to the anthers being basifixed and having a gland at their apex and not the flower on this occasion)

Pavonina: (pavonina is Latin for to be like a peacock. It refers to the showy flowers being very conspicuous contrasting the foliage.)

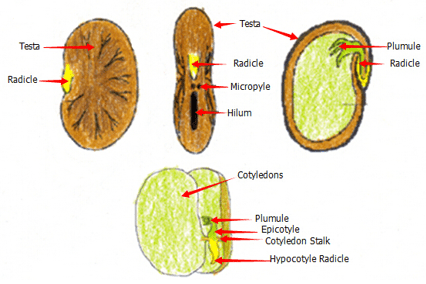

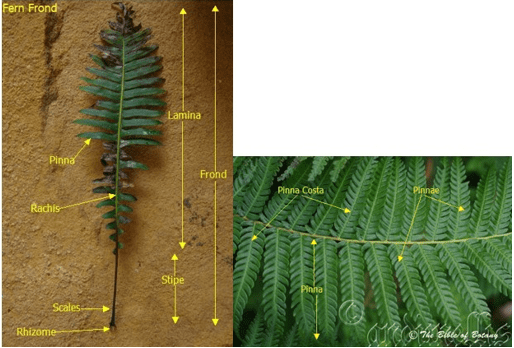

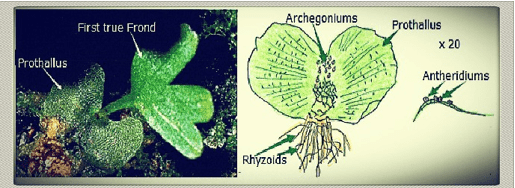

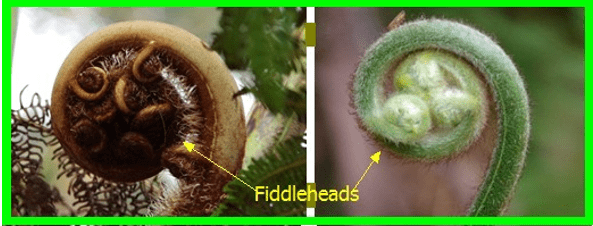

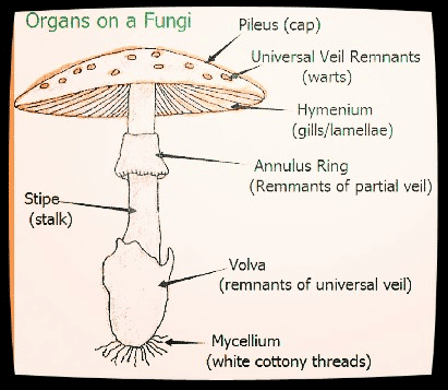

Before looking at the individual plant names, below I have outlined the basics in flora structure as the beginning of how plants are dscribed.

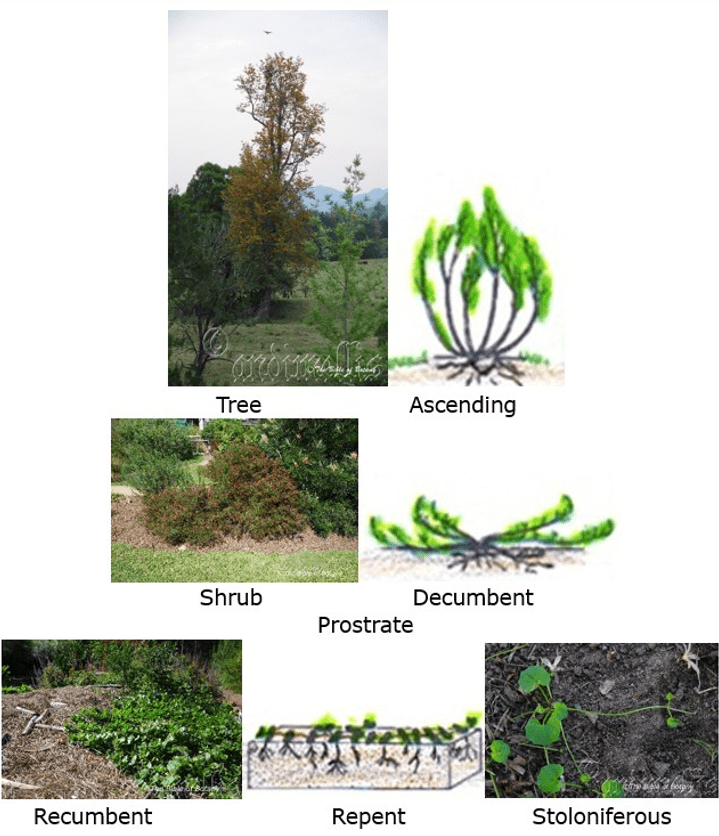

Growth Habits:

Drawings modified from the original as published in Swink F. and G. Wilson 1994 Plants of the Chigago region 4th edition Indionapolis Indiana Academy of science. Photos – andi Mellis

Ascending: Rising or curving upwards growing erect after an oblique or semi-horizontal beginning near the base.

Decumbent: From d?cumb?, which is Latin for a plant, which lies on the ground or over nearby low plants with its apexes turned upwards and its basis originating near the ground.

Prostrate: From pr?str?tus, which is Latin for any trailing plant growing over the ground or near by low shrubs

Recumbent: Resting on the surface of the ground or on low growing adjacent plants from near where it arises.

Repent: Is a prostrate growth along the ground in which roots develop at the nodes.

Stoloniferous: Is where stolons, also known as runners, are horizontal connections between organisms. They may be part of the organism, or of its skeleton.

Shrub: A perennial woody plant, differentiated from a tree by its smaller size, typically less than twice head height, usually with many branches and foliage emminating along the branches.

Tree: A perennial woody plant, differentiated from a shrub by its larger size, typically twice head height, usually with a single or few main axis or trunk unbranched for some distance above the ground and a head of branches and foliage.

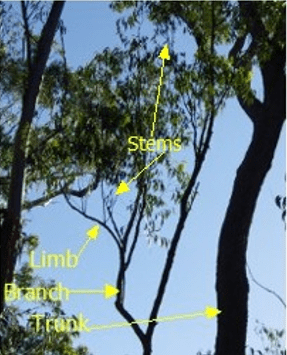

Stem, Root Types & Structure

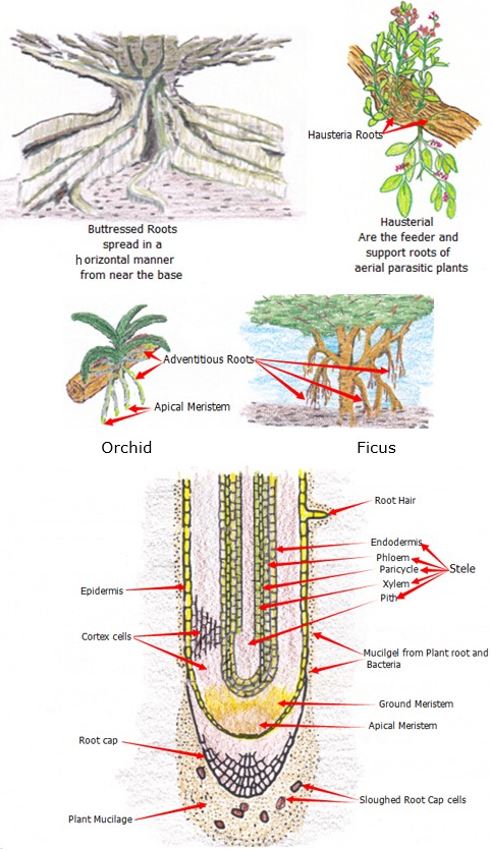

Adventitious: Are arial roots arising or descending from a tree that start above the ground. They include the roots of orchids.

Aerate or Knee: Are roots, which arise above the ground that do not contain specialised breathing pores.

Apical meristem region: Is the active growth region of the root. The leading section produces new root cap cells as old ones are discarded. The ground cells are completely indeterminate meristem cells in a plant that form three kinds of primary meristems. The primary meristems will eventually produce the vascular bundle cells, cortex cells and lateral growth cells.

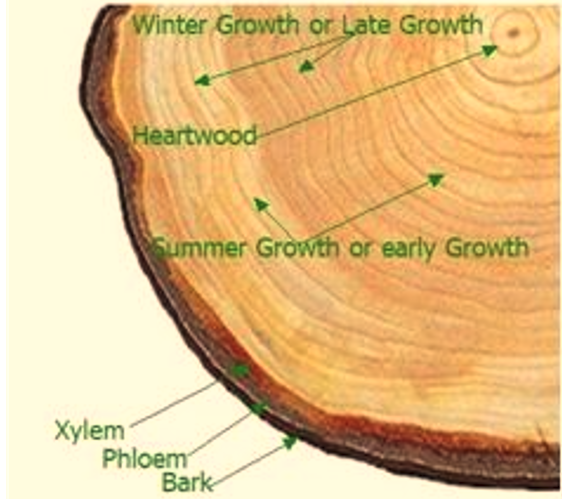

Bark: It is the outermost layer of stems and roots of woody plants. It refers to all the tissues outside the vascular cambium and is a nontechnical term. It overlays the wood and consists of the inner bark and the outer bark.

Buttressed: Are large, usually broad roots on all sides of generally shallowly rooted trees. Typically, they are found in more nutrient-poor tropical or subtropical forest soils. They prevent the tree from falling over; hence the name buttress, while trapping the maximum quantities of leaf litter, top soil and other debris.

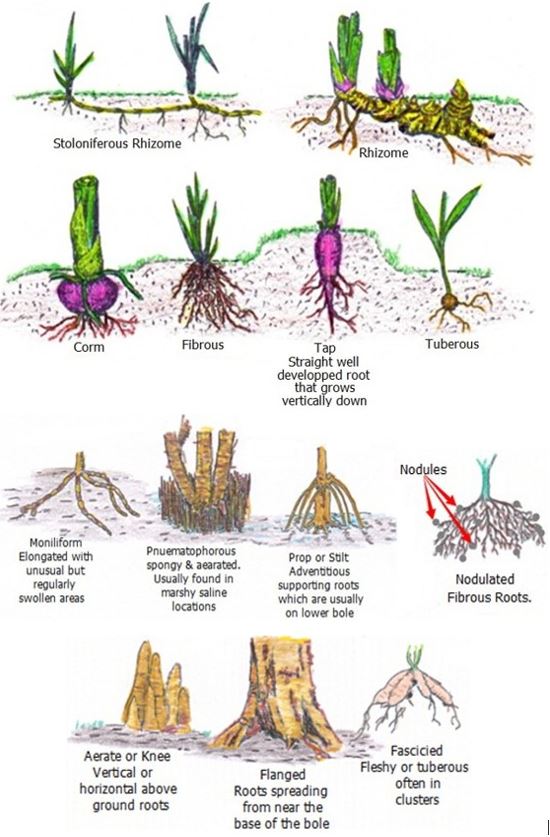

Corm: Are bulbo-tubers, and are short, vertical, swollen underground plant stems that serve as a storage organ for some plants. They have a basal plate where the roots emerge and are used to survive winter or at time to survive extended dry periods.

Cortex: The cortex is the outermost layer of the stem or root of a plant, between the epidermis on the outside and the endodermis on the inside. It comprises mostly of differentiated cells, usually large thin walled parenchyma cells in the green parts. The outer cortical cells often acquire irregularly thickened cell walls, and are called collenchyma cells. Some of the outer cortical cells may contain chloroplasts in the leaves. In the roots it is responsible for the transportation of materials into the central cylinder of the root through diffusion and may also be used for food storage in the form of starches.

Fascicied or Tuberous: From Tubor, which is Latin for roots, which are similar to corms in that they are short, vertical, swollen underground plant stems that serve as a storage organ for some plants. They do not have a basal plate where the roots emerge and are used to survive winter or at time to survive extended dry periods.

Epidermis: is a single layer of cells that covers the plant’s leaves flowers, roots and stems where it forms a boundary between the plant and the external environment. The epidermis serves several functions protecting the inner cells, secreting metabolic compounds and absorbs water and mineral nutrients.

Fibrous: Are roots, which have numerous, very fine branches of approximately the same length and re branch originating at a single point.

Flanged: Are flattened or expanded extensions of the margins at the base of a trunk.

Hausterial: From haustor, which is Latin for drank or sucked. It refers to roots of parasitic plants that are modified to penetrate the xylem of its hosts and retrieve water and nutrient from the host.

Heartwood: It is also known as duramen, dead, central wood of trees. Its cells usually contain tannins or other substances that make it dark in colour and sometimes aromatic. One or more layers of living and functional sapwood cells are periodically converted to the more physically strong heartwood.

Moniliform: From monolia, which is Latin for a jewel. It refers to roots , which have a long or short chain resembling a series of lumps, swellings, joints or nodes.

Nodulated: Are roots with small, swollen lumps, usually located on legumes in which nitro-fixing bacteria live in synogisum with the host.

Phloem: From phlóos, which is Ancient Greek for bark. It refers to the living tissue in vascular plants that conducts food from the leaves and other photosynthetic tissues to other organs in the plant. The phloem consists of several different kinds of cells including sieve elements, parenchyma cells, sclereids, and fibres. It is located on the inside of the bark.

Pneumatophorous: From pneumatikós which is Ancient Greek for relating to wind or air movements and phora, which is Ancient Greek for to bear or to carry. They are roots, which arise from below the surface and rise above the ground especially in terrains, which are waterlogged and differ from Aerial roots in that they contain specialised breathing pores, thus allow air movement between the plants roots and the atmosphere.

Prop or stilt: Are two types of adventitious roots with specific functions. Prop roots develop from horizontally spread branches of the tree growing vertically downwards, while stilt roots arise from basal nodes of the vertical stem initially growing horizontal before growing obliquely and finally vertically downwards to the soil to give additional support to the branch or trunk.

Rhizomes: From rhíz?ma, which is Ancient Greek for a mass of roots. They are modified subterranean, usually horizontal plant stems that send out roots and shoots from their nodes.

Stoloniferous rhizomes: From stol?, which is Latin for a shoot, branch, or twig springing from the root or stock of a tree; a sucker and From rhíz?ma, which is Ancient Greek for a mass of roots. A shoot that grows along the ground and produces roots at its nodes commonly known as a runner.

Tap root: Is a large, central, and dominant root from which other more hair like roots sprout laterally. They are somewhat straight and very thick, tapering in shape, and grow vertically downwards.

Tuberous: From Tubor, which is Latin for roots, which are similar to corms but have their roots growing from various places. They do not have a basal plate. They are short, vertical, swollen underground plant stems that serve as a storage organ for some plants. They appear randomly along the root system.

Xylem: From xúlon, which is Ancient Greek for wood. It refers to living tissue in vascular plants that carries water and dissolved minerals from the roots and provides support for softer tissues. The xylem consists of several different types of cells including fibres for support, parenchyma for storage, and tracheary elements for the transport of water.

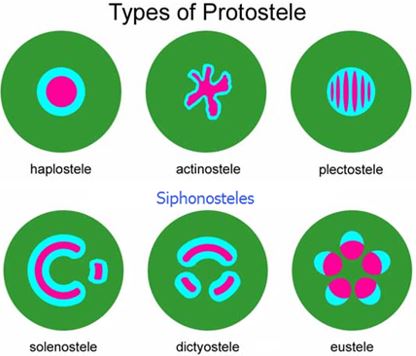

Actinostele: From actis, which is Ancient Greek for a ray or radial and st?l?, which is Ancient Greek for a column or shaft. The core of the vascular tissue in the stem extends outward in lobes.

Dictyostele: From díktuon, which is Ancient Greek for a net and st?l?, which is Ancient Greek for a column or shaft. The vascular tissue in the stem forms a central cylinder around a pith, but with closely spaced leaf gaps.

Eustele: From eû, which is Ancient Greek for well or good and st?l?, which is Ancient Greek for a column or shaft. The vascular tissue in the stem forms a central ring of bundles around a central pith.

Haplostele: From haplóos, which is Ancient Greek for a single, one or simple and st?l?, which is Ancient Greek for a column or shaft. The core of vascular tissues in the stem is smooth, without lobes or mixing of the tissues.

Plectostele: From plék?, which is Ancient Greek for to fold or weave and st?l?, which is Ancient Greek for a column or shaft. The two types of vascular tissue in the stem are intermingled.

Protostele: From pr?to, which is Ancient Greek for first or before and st?l?, which is Ancient Greek for a column or shaft. The vascular tissue in the stem forms a solid core, with no central pith or leaf gaps.

Siphonostele: From síph?n, which is Ancient Greek for a pipe or hollow tube and st?l?, which is Ancient Greek for a column or shaft. The vascular tissue in the stem forms a cylinder surrounding a central pith and possessing leaf gaps.

Solenostele: From s?l?n, which is Ancient Greek for tubes and st?l?, which is Ancient Greek for a column or shaft. The vascular tissue in the stem forms a central cylinder around a pith, with widely spaced leaf gaps.

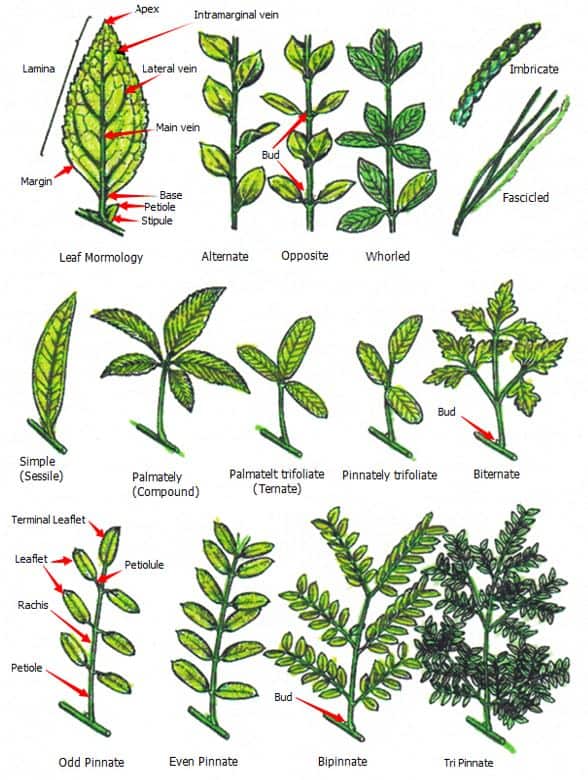

Leaf & Frond Types

Leaf Positions on Stems

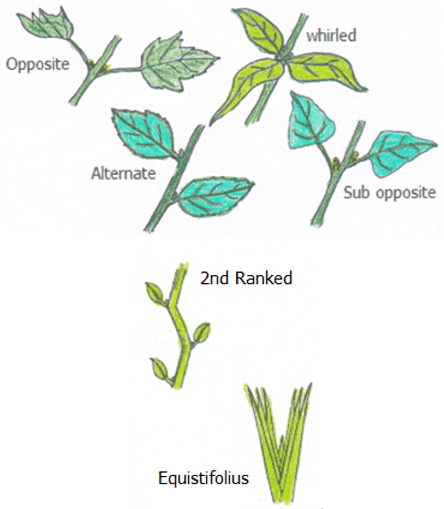

2nd Ranked: 2nd ranked describes leaves that alternate or 180 degrees on the two sides of the twig. It refers to the third leaf being found directly above the first leaf and the fourth leaf is on the other side of the twig, directly above the second leaf. Consequently 3rd rank is similar but with each leaf being 120 degrees around the stem the fourth leaf is found directly above the first leaf.

Alternate: Describes leaves that appear alternately or 180 degrees on the two sides of the twig.

Biternate: It refers to leaves, which have leaflets or other parts that are further subdivided in a ternate arrangement -threes. therefore biternate leaves are double ternate – with the ternate divisions again ternately divided.

Equistifolia: From equus, which is Latin for a horse and Foliage, which is Latin for foliage. It refers to foliage, which resembles a horse’s tail.

Even pinnate: Are compound leaves, which have an even number of leaflets along the rachis and has no terminal leaflet.

Fasicled: From fasciulus, which is Latin for a bundle. Growing in a bundle, tuft, or close cluster as are the leaves in the common pine tree.

Imbricate: From imbricatum which is Latin for tiles or tiling. flower bud in which the margins of petals and sepals within the flower bud or the leaves along the stem are overlapping in that one or more of the petals, sepals or leaves margins are the adjacent one.

Odd pinnate: Are compound leaves, which have an even number of leaflets along the rachis and has a terminal leaflet making the odd number.

Opposite: From oppositus, which is Latin for to be opposing to. It is where the leaves are at 180 degrees apart and at the same level on the stem.

Palmate trifoliate ternate: Are plants which have leaves with the three leaflets attached to a common point like the fingers of a human hand.

Palmately compound: Are plants which have leaves , which have four or more, usually five, seven or nine leaflets attached to a common point like the fingers of a human hand.

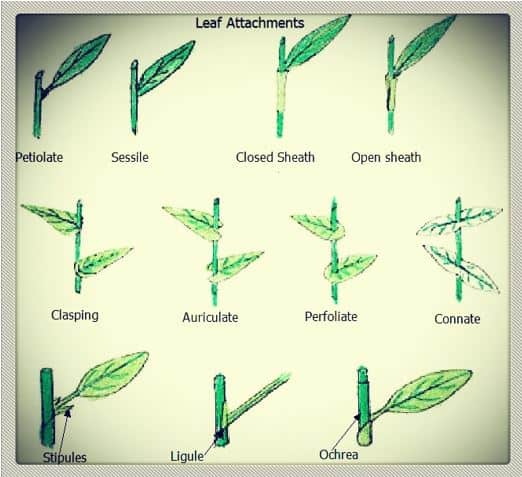

Petiolate: From petiol?tum, which is Latin for a little foot. It refers to leaves, which have short petioles.

Pinnately trifoliate: Are plants which have leaves with the three leaflets of which two are attached to a common point and the third has a petiole.

Rosette: Are leaves, which radiate in patterned clusters, usually close to the ground at the base of a plant.

Sessile: From sessile, which is Latin for a seat. It refers to leaves, which are seated directly on the stems, without a petiole.

Sub-opposite: From oppositus, which is Latin for to be opposing to. It is where the leaves are at 180 degrees apart and almost at the same level on the stem.

Sub-sessile: From sessile, which is Latin for a seat. It refers to leaves, which are seated almost on the stems, having a short petiolule.

Tripinnate: Are compound leaves, with lamina pinnately divided three times, i.e. the pinnules are again pinnately divided and then divided for a third time.

Whirled: Is where a ring of 3 or more leaves, bracts or floral parts are borne at the same level on a stem or axis.

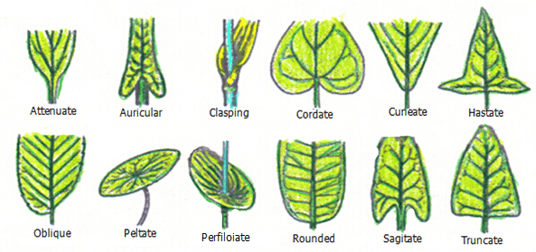

Leaf Attachments

Auriculate: From auricul?tum, which is Latin for to have an ear. It refers to leaves, which are attached like an ear to either side of the stem.

Clasping: It denotes where a leaf’s base partially or completely surrounds it’s stem.

Closed Sheath: A structure at the base of a leaf’s petiole that completely surrounds or protects the stem or at times another organ that it subtends.

Connate: It is the developmental fusion of organs of the same type being fused or united around the stem.

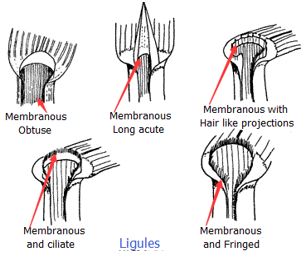

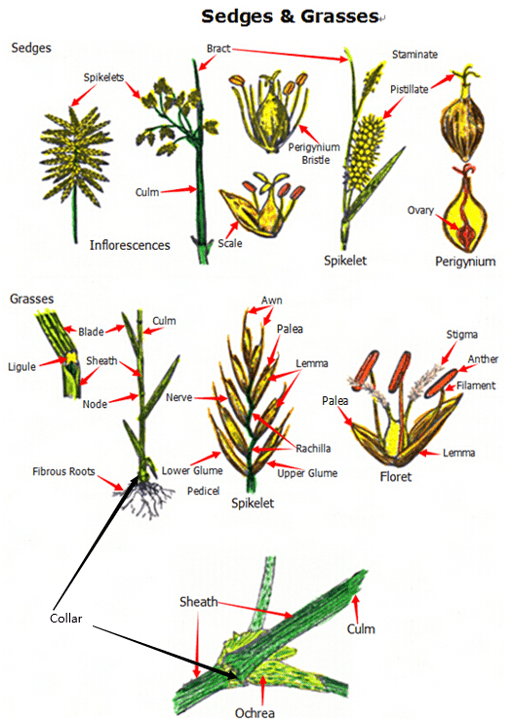

Ligule: Is the membranous appendage that arise from the inner surface of the leaf at the point with the leaf sheath in many grasses and sedges. The ligule is an important identification characteristic.

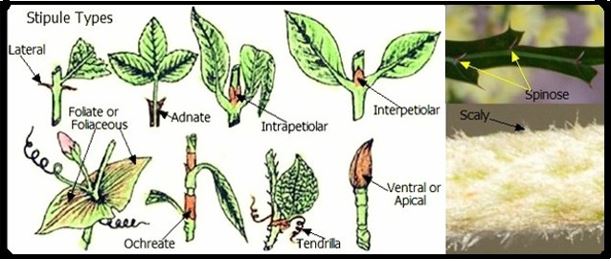

Ochrea: From ochrea, which is Latin for to greave or protective legging. It is a plant structure formed of stipules fused together into a sheath surrounding the stem. In palms it denotes an extension of the leaf sheath beyond the petiole insertion and is known as the rameal sheath.

Open sheath: A structure at the base of a leaf’s petiole that partially surrounds or protects the stem or at times another organ that it subtends.

Perfoliate: Is where a leaf appears to have the stem, which seems to pass through the blade. More often seen in immature leaves and on epicormic regrowth.

Petiolate: From petiol?tum, which is Latin for a little foot. It refers to leaves, which have short petioles.

Sessile: From sessile, which is Latin for a seat. It refers to leaves, which are seated directly on the stems, without a petiole.

Stipules: Are any outgrowths borne on either side; or at times just on one side, of the base of the petiole. A pair of stipules is considered part of the anatomy of the leaf of a typical flowering plant, although in many species the stipules are inconspicuous or entirely absent. – exstipulate (“ex” which is Ancient Greek /Latin for without or not having).

Ligules

Membranous: Is to have the characteristic or appearance of being thin, rather soft, pliable, and often translucent or opaque.

Ciliate: From cili?tum, which is Latin for short fine hairs. A structure, which has a fringe with fine hairs.

Fringed: A structure, which has longer and courser hairs than ciliate.

Hair like: A structure, which has a long course scattered hairs.

Long acute: Refers to the shape of the membrane being rather long and arrow shaped.

Obtuse: Refers to the shape of the membrane being round.

Types of Stipules

Right Parsonia straminea with grappling adventurous roots and suction pad

Right Cissus antarctica with leaf opposed bifid tendril – andi Mellis

Right Parasitic Cassytha pubescens with stem suction pad – andi Mellis

Tendril: Is a slender threadlike appendage of many climbing plants, often growing in a spiral form, that stretches out and twines around any suitable support.

Bifid: Refers to the tendrils dividing into two extended tendrils.

Leaf opposed: Is where the tendril emerges on the opposite side to the leaf.

Petiole tendril: Is where the leaf’s petiole attaches itself to another structure for support.

Simple: Is where the tendril does not divide further and often form tight coils.

Suction Pads: A special organ for attaching to a non-porous surface by means of adhering to non porous surfaces or sucking, especially deployed by parasitic plants for entering the xylem of its host plants.

Trifid: Refers to the tendrils dividing into three extended tendrils.

Twinning: Refers to stems that twist around adjoining structures.

Leaf & Petals Shapes

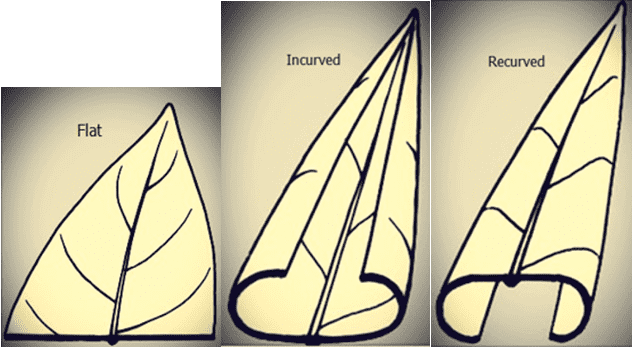

Incurved: Is to bend upwards from the midvein to the margins.

Recurved: Is to bend downwards from the midvein to the margins.

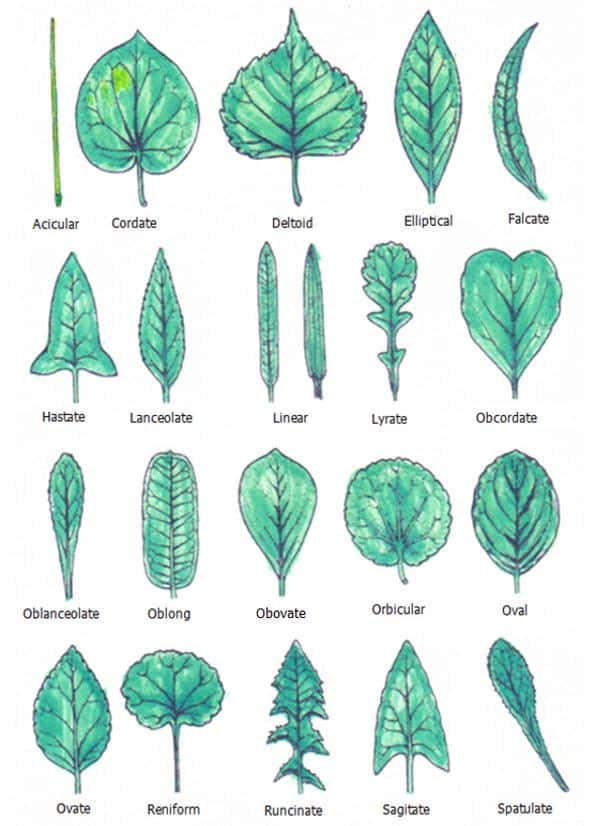

Acicular: From acicula, which is Latin for a hairpin or to be needle like. It refers to leaves, which have the form of a needle.

Cordate: From cord?tum which is Latin for heart shape. It refers to a leaf Blade, which is broad and notched at the base, thus is heart-shaped.

Deltoid: From deltoeid?s, which is Ancient Greek for a triangle shape. It refers to an organ, which is triangular or roughly triangular in shape. Different from cordate in that it has a truncate base.

Elliptical: From elleiptikós, which is Ancient Greek for tp have an oval form . It refers to having a general shape; usually a leaf, that has an elliptic form with relatively pointed at both ends.

Falcate: From falc?tum, which is Latin for curved, hooked or sickle shaped. It refers to structures that shaped like a scythe.

Hastate: From hast?tum, which is Latin for a spear. It refers to structures that are shaped like an arrow head.

Lanceolate: From lanceol?tum, which is Latin for a lance. It refers to leaves that are typically shaped like a lance.

Linear: From l?ne?re, which is Latin for to have lines. It refers to leaves that have parallel or almost parallel sides.

Lyrate: From lúra, which is Ancient Greek or later lyr?tum, which is Latin for a lyre. It refers to leaves that somewhat resemble the ancient lyre.

Obcordate: From ob, which is Latin for against or a reverse shape and cord?tum which is Latin for heart shape. It refers to a leaf Blade, which is broad and notched at the apex and tapers at the base, thus is a reverse heart-shaped.

Oblanceolate: From ob, which is Latin for against or a reverse shape and lanceol?tum, which is Latin for a lance. It refers to leaves that are typically shaped like a lance with the broad end at the apex and tapers at the base, thus a reversal of lanceolate.

Oblong: It refers to leaves, which are somewhat rectanglar in having the length greater than width, with rounded cornes and parallel sides.

Obovate: From ob, which is Latin for against or a reverse shape and ?ión, which is Ancient Greek or later ?wom, which is Latin for an egg or to take the form of an egg. It refers to leaves that are egg shaped with the broader end at the apex.

Orbicular: From orbicul?re, which is Latin for to be circular. It refers to leaves that are round.

Oval: From ?ión, which is Ancient Greek or later ?wom, which is Latin for an egg or to take the form of an egg. It refers to leaves that are roughly egg shape with both the base and apex being roughly similarly rounded.

Ovate: From ?ión, which is Ancient Greek or later ?wom, which is Latin for an egg or to take the form of an egg. It refers to leaves that are egg shaped with the broader end at the base.

Palmate: From palma, which is Latin for the palm of the hand. It refers to leaves that are palm shaped with shallow or deep lobes.

Reniform: From phr?n, which is Ancient Greek for roughly heart shape or later r?n, which is Latin for to be kidney shape and form. It refers to leaves that are kidney shape or at times between a kidney and heart shape.

Runcinate: It refers to leaves, which have a lacerated aspect with the projections pointing away from the apex and gradually tapering towards the apex.

Sagittate: From sagitta, which is Ancient Greek or later sagitta, which is Latin for to shoot an arrow. It refers to leaves that are strongly shaped like an arrow head. Spatulate: From spatul?tum, which is Latin for a spatula or spoon. It refers to leaves that have a broad rounded apex with a narrow base, un-subdivided, simple and spoon shaped.

Leaf Margins

Academy of science.

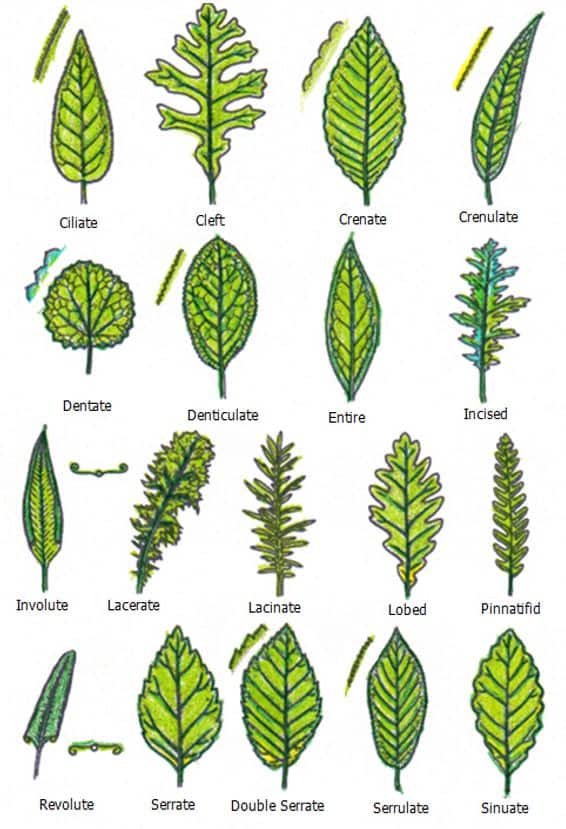

Ciliate: From cili?tum, which is Latin for short fine hairs. A structure, which has a fringe with fine hairs.

Cleft: To have indentations that extend about halfway to the midvein from the margins.

Crenate: From cr?n?tum, which is Latin for a notch. It refers to an organ’s margins, which have a series of small rounded notches.

Crenulate: From cr?n?tum, which is Latin for a notch. It refers to an organ’s margins, which have a series of very small rounded notches.

Dentate: From dent?tum, which is Latin for to have teeth. It refers to structure margins, which have a series of teeth.

Denticulate: From dent?tum, which is Latin for to have teeth. It refers to an organ’s margins, which have a series of rather fine teeth.

Entire: To have a smooth margin without any indentations.

Incised: To have margins, which are sharply, deeply, and somewhat irregularly notched.

Involute: From invol?tum, which is Latin for to curl upwards. It refers to leaves which roll upwards near the margins on the upper lamina.

Lacerate: From lacer?tum, which is Latin for to mutilate or rip to shreds. It refers to an organs margins, which appear to have been ripped to shreds.

Lacinate: From lacini?tum, which is Latin for to irregularly and finely slash. It refers to an organs margins, which appear to have been irregularly and finely slashed.

Lobed: It refersto leaf margin, which have rounded segments that has the shape or form of an ear lobe.

Pinnatifid: To have clefts, which almost reach midrib in broad divisions, but not separated into distinct leaflets.

Revolute: From revol?tum, which is Latin for to revolve. It refers to leaves which roll downwards near the margins on the lower lamina.

Serrate: From serr?tum, which is Latin for to saw up. It refers to an organ’s margins, which have teeth that resemble a saw.

Double serrate: From serr?tum, which is Latin for to saw up. It refers an organ’s margins, where the margins have teeth that resemble a fine saw.

Serrulate: From serr?tum, which is Latin for to saw up. It refers to an organ’s margins, where the margins have minutely fine.

Sinuate: From sinu?tum, which is Latin for a curve, fold or bend. It refers to an organ’s margins, where the margins have curves or appear like wave on the beach.

Leaf Apex, Venation & bases

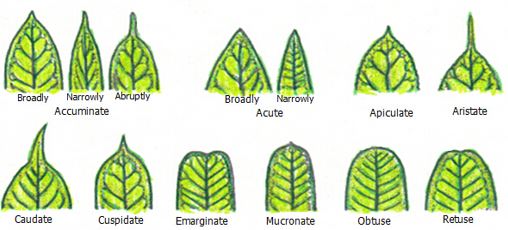

Accuminate: Tapering to an extended point in concave manner at its apex. There are three divisions of accuminate apexes, – Broadly, Narrowly and Abruptly

Acute: From ac?tum, which is Latin for sharpened or to make sharp. It refers to apexes, which taper evenly to a point, with the converging edges forming an angle. There are two forms, – Broadly and narrowly.

Apiculate: From apicul?tum, which is Latin for a bishop’s hat or an abrupt point. It refers to apexes, which resemble a priest’s cap, or a helmet or crown.

Aristate: From arist?tum, which is Latin for to have an awn like on a cob of corn. It refers to leaf apexes, which end in a long, rigid awn.

Caudate: From caud?tum, which is Latin for to have a tail. It refers to leaf apexes, which taper off like a tail.

Cuspidate: From cuspis, which is Latin for to a point or a sting. It refers to leaf apexes, which have a short often sharp point.

Emarginate: From Ex, which is Latin for without and margino, which is Latin for to deprive something of its edge. It refers to leaf apexes, which are more or less truncate and have a small notch.

Mucronate: From m?cr?n?tum, which is Latin for a sharp point as in a spine. It refers to leaf apexes, which truncate apexes which have a short,sharp spine.

Obtuse: From obt?sum, which is Latin for rounded. It refers to leaf apexes, which are rounded.

Retuse: From ret?sum, which is Latin for rounded. It refers to leaf apexes, which are rounded or obtuse and have a small notch.

Attenuate: From attenu?tum, which is Latin for to reduce, thin down or make weak. It refers to leaf bases, which taper forming a thin wing along part of the petiole.

Auricular: From auricul?re, which is Latin for pertaining to an ear. It refers to leaf bases, which appear to have an ear lobe either side of the petiole.

Clasping: It refers to a leaf base, which partially or wholly surrounds a stem.

Cordate: From cord?tum which is Latin for heart shape. It refers to a leaf Blade, which is broad and notched at the base, thus is heart-shaped.

Cuneate: From cuneus, which is Latin for a wedge. It refers to leaf bases, which taper like a wedge to or near the petiole.

Hastate: From hast?tum, which is Latin for to be armed with a spear. It refers to leaf bases, which resemble a spear.

Oblique: From obl?quum, which is Latin for to be slanted or uneven. It refers to leaf bases, which have the blade asymmetrical. That is one side is larger or extends further along the petiole than the other side.

Peltate: From pelt?tum, which is Latin for a small often crescent shape shield. It refers to leaves, which has the petiole joining the leaf in the middle of the lower lamina.

Perfoliate: From per, which is Latin for through and folium, which is Latin for foliage. It refers to leaves, which appear to have the stem passing through the leaf near the base.

Rounded: It refers to leaf bases which are round or semi circular.

Sagitate: From sagitta, which is Ancient Greek or later sagitta, which is Latin for to shoot an arrow. It refers to leaf bases, which are strongly shaped like the base of an arrow head.

Truncate: From trunc?tum, which is Latin for maimed or had a limb cut off. It refers to leaf bases, which appear to have been cut off square.

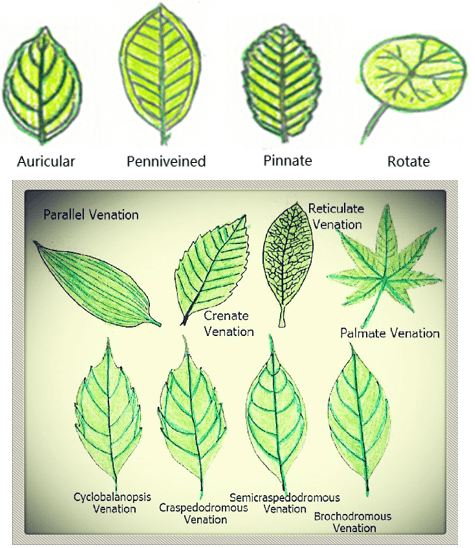

Auricular: From auricul?re, which is Latin for pertaining to an ear. It refers to leaf bases, which appear to have an ear lobe either side of the petiole.

Brochodromous: From Brochno, which is Ancient Greek for the gums or a palate and drómos, which is Ancient Greek for a race or running. It refers to the lateral veins, which run along side the margin.It describes a single midvein with the lateral veins arising from the midvein and curve upwards towards the margin. The lateral veins run parallel to the margin before making a marginal loop.

Camptodromous: See Semicraspedodromous.

Crenate: From cr?n?tum, which is Latin for a notch or scallop like edges of the leaf. It refers to the lateral veins, which run at an angle upwards from the midvein and finish adjacent to notches or run into the notch on the leaf’s margin.

Craspedodromous: From craspedota, which is Latin for a narrow shelf-like ridge or line on the inner border of the margin and drómos, which is Ancient Greek for a race or running. It refers to the lateral veins, which finish adjacent to notches on the leaf’s margin.

Cyclobalanopsis: From kuklikós, which is Ancient Greek or Cyclic, which is Latin for a circle, balan, which is Ancient Greek for an acorn or penis and ópsis, which is Ancient Greek for an aspect or appearence of. It may refer to the lateral veins, which appear to encircle the margins and have an extension that extends through to the margins.

Palmate: From palma, which is Latin for the palm of the hand. It refers to leaves that are palm shaped with shallow or deep lobes. The main veins extend out from the base to the apex of each lobe, with the lateral veins curving upwards towards the margin. Most palmate venation display reticulate venation on the lobes however some display a poor parallel venation.

Parallel: Is seen in leaves where all the veins of a leaf are parallel to each other. In such leaves, the veins usually run parallel to each other from the base of the leaf to the apex of the leaf. Parallel venation is usually found on linear leaves of dicotyledon plants and monocotyledon plants are almost entirely parallel venation except for a few that have reticulate venation.

Penniveined: It refers to the lateral veins, which branch off the mid vein at a straight angle upwards from the midvein and form a distinct loop inside the leaf’s margin leaf’s margin. The intramarginal veins may or may not start and finish at the same level.

Pinnate: It refers to the lateral veins, which branch off the mid vein at a straight angle upwards from the midvein and peter out prior to reaching the leaf’s margin without forming a loop.

Reticulate: From r?ticul?tum, which is Latin for a net. It refers to lateral veins, which are not prominent and further divide giving the appearance of a net or spider’s web.

Rotate: From rot?tum, which is Latin for to spread out like the spokes of a wheel. It refers to lateral veins, which radiate from a central point like the spokes of a wheel and often have a reticulated venation between the lateral veins. Most rotate venation leaves display reticulate venation between the main lateral veins however some display a poor parallel venation.

Semicraspedodromous: From Brochno, which is Ancient Greek for the gums or a palate and drómos, which is Ancient Greek for a race or running. It refers to the lateral veins, which run along side the margin. It describes a single midvein with the lateral veins arising from the midvein and curve upwards towards the margin. The lateral veins unite in a series of conspicuous loops inside the margin.

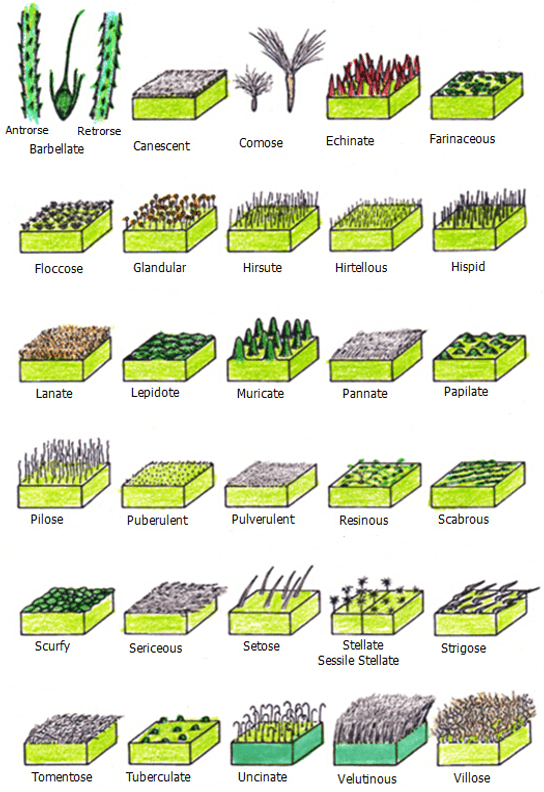

Leaf & stem Surface Features

Modified from the original as published in Swink F. and G. Wilson 1994 Plants of the Chigago region 4th edition Indionapolis Indiana

Academy of science

Barbellate: is to have a covering of short stiff hooked bristles, barbs, quills, spines or thorns. They may be antrorse or retrorse.

Antrorse: Is where the barbs curve forward and upward towards the apexes.

Retrorse: Is where the barbs curve backward and downward towards the bases.

Canescent: From c?num, which is Latin for to become white, grey or hoary as if growing old. It refers to surfaces, which have a white, grey or hoary aging appeal.

Comose: From com?sum, which is Latin for to have ample long hair. It refers to surfaces usually the apex of seeds, which have long hairs.

Echinate: From echin?tum, which is Latin for to be prickly as in an echidna. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in short sharp spines.

Farenaceous: It refers to having a floury with a somewhat grainy texture.

Floccose: From flocc?sum, which is Latin for tufts of wispy wool. It refers to surfaces, which consist of tufts of woolly, soft hairs.

Glandular: From gl?ns, which is Latin for an acorn. It refers to surfaces, which consist of hirsute or hirtellus type hairs with an enlarged gland at the apex. The glands are often exude a sticky substance.

Hirsute: From H?rs?tum, which is Latin for haairs that are rough, shaggy, somewhat bristly or prickly to touch. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in rough, shaggy, somewhat bristly or prickly to touch hair like a week old beard. They are longer than hirsute and less rigid than hispid hairs.

Hirtellous: From h?rtum, which is Latin for short hairs that are rough, shaggy, somewhat bristly or prickly to touch. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in rough, shaggy, somewhat bristly or prickly to touch hair like a three or four day old beard. They are shorter than hirsute and less rigid than hispid hairs.

Hispid: From hispidum, which is Latin for hairs that are rough, shaggy, bristly and prickly to touch. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in rough, shaggy, bristly or prickly to touch hairs. They are longer than hirsute hairs and much more rigid.

Lanate: From l?n?tum, which is Latin for hairs that have woolly to downy texture. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in thick layer of soft wooly to downy hairs.

Lepidote: From lepid?tós, which is Ancient Greek for to be covered with scurfy like scales. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in a dense layer of rather flat scurfy like scales.

Muricate: From m?ric?tum, which is Latin for to have blunt, rigid points. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in blunt, rigid mounds or points.

Pannate: It refers to surfaces, which are covered in short, fine silky antrorse or retrorse appressed hairs.

Papillate: From papill?tum, which is Latin for to have a nipple or bud. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in minute bumps similar to those found around a nipple.

Pilose: From pil?sum, which is Latin for to have long, shaggy hairs. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in long wavy slightly stiffened hairs.

Puberulent: From puber, which is Latin for downy and ulentus, which is Latin for abounding in. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in short, soft, downy like hairs.

Pulverulent: From pulverulentum, which is Latin for turning to dust. It refers to surfaces, which have a powdery or dusty texture.

Resinous: From r?s?n?sum, which is Latin for resinous. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in resin or other similar highly viscous substances.

Scabrous: From scabrum, which is Latin for scabby, mangy or itchy. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in short mangy or scabby looking hairs.

Scurfy: It refers to surfaces, which are covered in minute membranous scales.

Sericeous: From s?rikós, which is Ancient Greek, s?ricum, which is Latin or s?res, which is Northern Chinese for silk or silky. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in appressed, long fine silky hairs or at times long, matted, fine silky hairs.

Setose: From s?t?sum, which is Latin for a bristle or bristly. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in long, thick rigid bristly hairs.

Stellate: From st?ll?tum, which is Latin for a star or starry. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in rigid hairs that have stellate apexes.

Sessile Stellate: From st?ll?tum, which is Latin for a star or starry. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in stellate hairs that are directly located on the surface.

Strigose: From striga, which is Latin for a furrow or a row. It refers to long stiff or rigid hairs akin to being hispid that are in distinct rows.

Tomentose: From t?ment?sum, which is Latin for long unkempt hairs. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in long often soft unkempt hairs.

Tuberculate: From t?bercul?tum, which is Latin for to have a warty appearance. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in uneven warty like lumps.

Uncinate: From unc?n?tum, which is Latin for to have hooks or barbs. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in hairs that have hooks or barbs at the apexes.

Velutinous: Having a layer of short, soft, velvet like hairs. Villose: From vill?sum, which is Latin for shaggy and unkempt. It refers to surfaces, which are covered in long, soft, unkempt hairs.

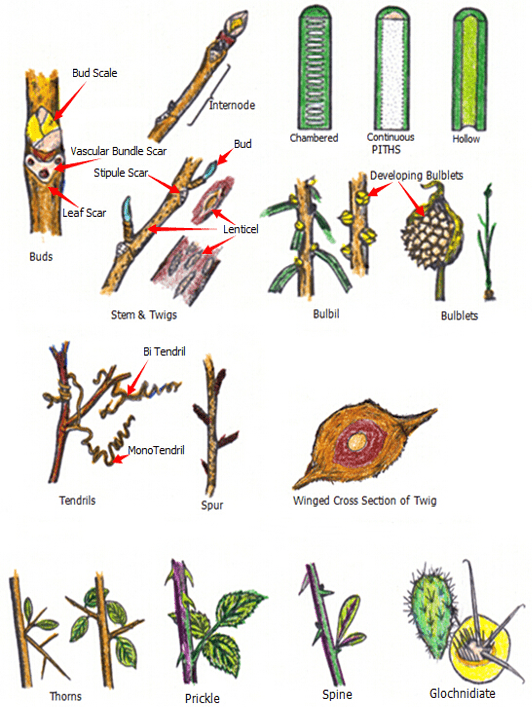

Stems & Leaf Variables

Academy of science.

Piths: Is the soft substance at the center of a plant’s stem. The pith comprises of soft, spongy parenchyma cells, which store and transport nutrients throughout the plant. In dicotyledons the pith is located in the center of the stem. In monocotyledons, it extends into the flowering stems and roots. The pith is encircled by a ring of xylem and the xylem, is encircled by an outer ring of phloem.

Chamber pith: It refers to a pith that has chambers in the stem caused by septations at right angles to the long or vertical axis.

Continuous pith: It refers to a pith that is continuous, without any septations along the long axis.

Hollow: It refers to a pith that does not exist or the pith in the middle of the stem may dry out and disintegrate, resulting in a hollow stem.

Glochindiate: From Glochindiate, which is Ancient Greek for to have barbs. It refers to surfaces, usually within an areola where these types of hairs emerge and grow.

Internode: Is the portion of a stem between the level of insertion of two successive leaves or leaf pairs or branches of an inflorescence. That is the segment of a stem between two nodes or the portion of stem found between lateral meristems in plants.

Leaf scar: Is the mark left by a leaf after it is discarded from the twig. It marks the site where the petiole was attached to the stem. A leaf scar is typically found below a branch as branches come from axillary buds located at the nodes immediately above the leaf scars.

Lenticel: One of the small, oval, rounded spots upon the stem or branch of a plant, from which the underlying tissues may protrude or roots may protrude, either in the air, or more commonly when the stem or branch is covered with water or earth.

Node: From n?dus, which is Latin for a knob or swelling. It refers to the point of attachment of a leaf or a twig on the stem in seed plants where new stems or flowers usually appear.

Prickle: Is a curved, pointed structure arising from the outer layer of a stem, leaf, etc, and containing no woody or conducting tissue.

Spine: From sp?nus, which is Latin for a type of thorn. A spine is a stiff rigid structure with a sharp point from a highly modified leaf, scale, or stipule. It usually contains vascular tissue and originate from the axil.

Spur: Is an accelerated growth or development of a stem or to outgrowths of tissue. The most common usage of the term in botany refers to nectar spurs in flowers.

Stipule scar: Is the mark left by stipules after they are discarded from the stem. It marks the site where the stipules were attached to the stem.

Thorn: Is a stiff rigid structure with a sharp point, modified from a stem. It occurs in the axil of a leaf where a stem would normally develop.

Vascular bundle: Is a complex transport system of water and minerals in vascular plants. The movement of water and minerals occur in the stems. This exists between the xylem -water and minerals from the roots to the green structures and the phloem – water and minerals in both directions to aid growth, stability and health. Both these tissues are present in the vascular bundle, which includes support and protective tissues. In dicotyledon plants the vascular bundles are situated in a ring near the outside of the stem, with the phloem on the outside of the xylem. In monocotyledons the bundles are scattered randomly.

Winged: There are three types of wings associated with botany.

* A membranous expansion either side of the seeds which aids in dispersal.

* A thin flange of tissue extending beyond the normal outline of a structure located on stems and petioles.

* Are the two lateral petals of a flower of subfamily Faboideae of family Fabaceae, located between the adaxial standard petal and the two abaxial keel petals.* A thin extention of growth on the column of many orchids.

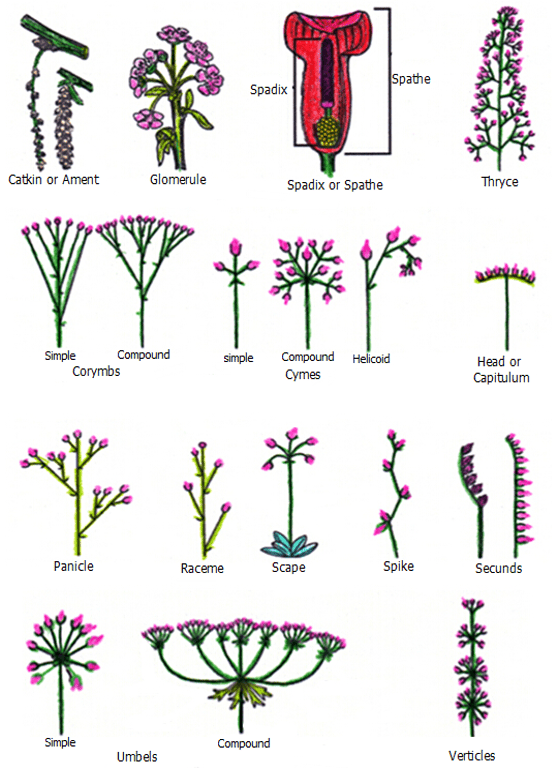

Inflorescence Arrangements

Academy of science.

Catkin or Ament: Is a type of spiked inflorescence, consisting of an axis with many unisexual, apetalous flowers along its sides, as in the foreign weeping willow.

Corymbes: From kórumbos, which is Ancient Greek or corymbus, which is Latin for a bunch of fruits, to peak or a summit. It refers to an inflorescence where the outermost flowers have the longer pedicels, while the inner flowers have progressively shorter pedicels so that all the flowers are at the same level. Flowers in a corymb layout can be either parallel, or alternate, and have either a convex, or flat top.

Cymes: From kûma, which is Ancient Greek or cyma, which is Latin for swollen or I conceive. It refers to an inflorescence usually with a flat top in which the central or lower flowers open first, followed by the upper or peripheral flowers.

Capitulum: From káput, which is Latin for a head. It refers to an inflorescence head composed of numerous tiny florets, associated with the Asteracea family.

Glomerule: From glomus which is Latin for a ball. It refers to an inflorescence head similar to a cymose inflorescence but having a more ball-like cluster of flowers.

Panicle: From p?nicula, which is Latin for an ear of millet or thread wound on a bobbin. It refers to a much branched inflorescence. Some authors distinguish it from a compound spike inflorescence, by requiring that the flowers be pedicellate in having a single stem per flower. The branches of a panicle are often racemes.

Raceme: From rháx, which is Ancient Greek or rac?mus, which is Latin for a bunch of grapes. Is an unbranched, indeterminate type of inflorescence bearing pedicellate flowers (flowers having short floral pedicels) along its axis. In botany, an axis means a shoot, in this case one bearing the flowers. (Maybe the original grapes before man’s interference were in fact racemes.)

Scape: Is a long, leafless internode that forms the basal part or the whole of a peduncle. It takes the form of a flowering stem rising directly from a bulb, rhizome, or similar subterranean or underwater structure often from the centre of a rosette of leaves.

Spadix: From sp??d?x, which is Ancient Greek or sp?d?x, which is Latin for a palm branch. Is a type of inflorescence spike which has small, apetalous flowers borne on a fleshy stem. The male and female flowers are separate with the male flowers ususally closer to the apex, while the female flowers are usually at the base.

Spathe: Is a bract or pair of large and colourful bracts, subtending or enclosing a spadix inflorescence.

Spike: Is a type of inflorescence that bears taller-than-average flowers, most usually on an axis that is unbranched. Similar to a raceme, the spike bears flowers that are sessile, without any peduncles and often have a zig zag pattern.

Secunds: From secundum, which is Latin for to follow or I follow. Is where the flowers or leaves are directed only to one side of the axis, that is they follow a straight line to one side.

Thryce: It refers to flowers of pinules, which are divided three times or thrice for a third time with the centre flower or leaflet usually being a single flower.

Umbels: From umbella, which is Latin for an umbrella. Is where the inflorescence that consists of a number of short flower pedicels, which spread from a common point, somewhat like the ribs of an umbrella ribs. There are simple umbels and compound umbels, where the inflorescenes make up several simple umbels on the same peduncle.

Verticles: From verticular, which is Latin for a joint. It is where the inflorescence have the flowers arranged in a seeming whorl along the axis. The opposite infloresences are usually sessile, cymes at the joint or nodes on the flowering spike.

1st Pedicel on the flower, 2nd Rachis, 3rd Pedunclulate, between the pedicel and the rachis on a Panicle 3rd or 4th Peduncule, from the stem to the rachis or pedunculate Digitate.

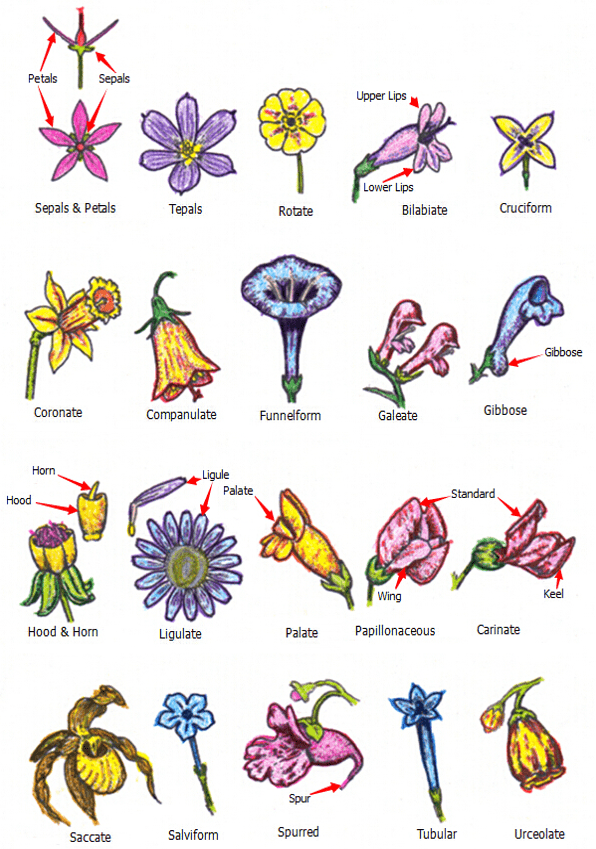

Corolla & Tubes

Academy of science.

Bilabiate: From bi, which is Latin for two and labiate, which is Latin for lips. Is where the inflorescence tube has a pair of lobes and the other three lobes distinctly in opposite positions on the corolla tube.

Carinate: Is to have the form or shape of a keel. It refers to the florescence of the Fabiaceae family, which have more prominent keel petals.

Coronate: From cor?n?re, which is Latin for a crown or to enclose. Is where the inflorescence tube is short and has a crown-like appendage at the apex.

Cruciform: From crux, which is Latin for a cross and Forme, which is Latin for to take the shape or form of. It refers to an inflorescence which has 4 petals or four dominant sepals that resemble a cross.

Companulate: From companulata, which is Latin for a bell. It refers to an inflorescence which resemble a typical bell.

Corolla: From cor?lla, which is Latin for a small garland or an object that encircles the head – chaplet. It refers to the structure and pattern made up by an inflorescen’s petals.

Funnelform: From fundibulum, which is Latin for a funnel and forme, which is Latin for to take the shape or form of. It refers to inflorescences, which have a form gradually widening from the base to the apex, like a funnel.

Galeate: From gale?tum, which is Latin for a helmet. It refers to inflorescences or calyx having the form of a helmet.

Gibbose: From gibb?sum, which is Latin for to have a hump. It refers to inflorescences, which have a rounded protuberance at the side or base.

Hood & Horn: Is to have a cap with a horn, which cover and protect the developing inflorescence.

Ligulate: From ligul?tum, which is Latin for to have a tongue. It refers to inflorescences in the Asteraceae family. If the two types of flower are in the same capitulum, the capitulum is called radiate; if only disk flowers are present, the capitulum is called disciform or discoid inflorescences; and where the ray flowers are present, the capitulum is called ligule.

Lips: The labellum or lip is the part of the inflorescence of an orchid or Canna, or at times another less-known genera, that serves to attract insects, which pollinate the flower. It acts as a landing platform for insects. It is often united with the column and can be hinged or movable, facilitating pollination.

Palate: It refers to a projection in the throat of a flower, which have a tube.

Papillonaceous: From p?pili?, which is Latin for a butterfly. It refers to inflorescences that are legumes or are in the Fabaceae family.

Petal: From pétalon, which is Ancient Greek for a thin metallic leaf. It refers to the modified leaves that surround the reproductive organs of flowers. They are usually brightly coloured, unusually shaped or larger in order to attract pollinators.

Saccate: From sacc?tum, which is Latin for a pouch. It refers to a modified petal that resembles pouch. They are usually brightly coloured to help attract pollinators.

Salviform: From salvia, which is Latin for well or unharmed and forme, which is Latin for to take the shape or form of. It refers to inflorescences that resemble those of the Salvia genus in that they are long, narrow and campanulate or resemble bells but are much longer and narrower.

Sepals: From s?palum, which is Latinized from the Ancient Greek words of s?par?tus, to separate and pétalon for a thin metallic leaf. It refers to that part of the inflorescences usually behind the petals, when they exist. They are found on the outermost part of the flower, and like a petal, a sepal is considered to be a modified leaf and are collectively known as the calyx.

Spurred: It refers to outgrowths of tissue on different plant organs that usually contain nectar as in nectar spurs in flowers or nectaries.

Tepals: Is one of the outer parts of a flower, collectively as the corolla. The term is used when these parts cannot easily be classified as either sepals or petals.

Tubular: It refers to an inflorescen that is formed with the sepals, petals, and stamens being united as one.

Urceolate: From urceolatus, which is Latin for an urn. It refers to inflorescences, which resemble a pot belly urn.

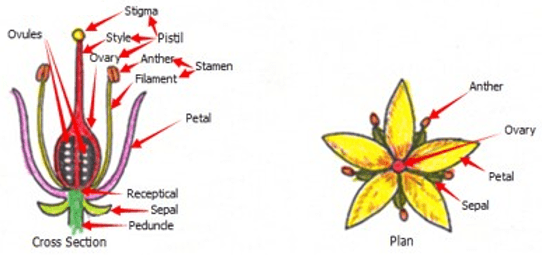

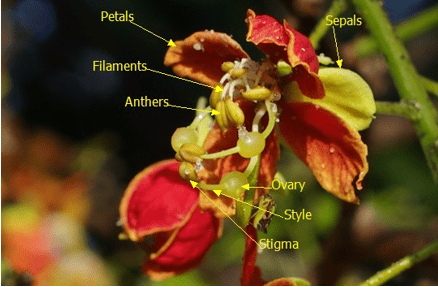

Floral Morphology

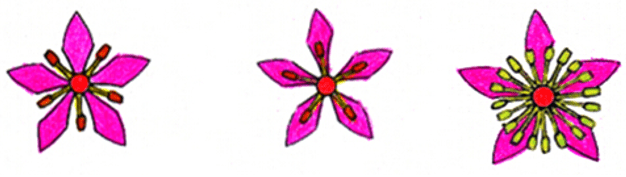

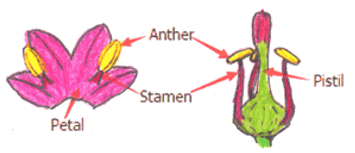

Anther: From ántha/ánthos, which are Ancient Greek for the male reproductive organs on a flower or the flower. Is that part of the stamen that produces and contains pollen and is usually borne on a stalk known as the filament.

Filament: From f?lum, which is Latin for a fine thread. It refers to a long slender cell or series of attached cells, as in some algae and fungi or the stalk like portion of a stamen, supporting the anther.

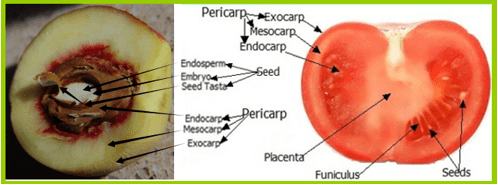

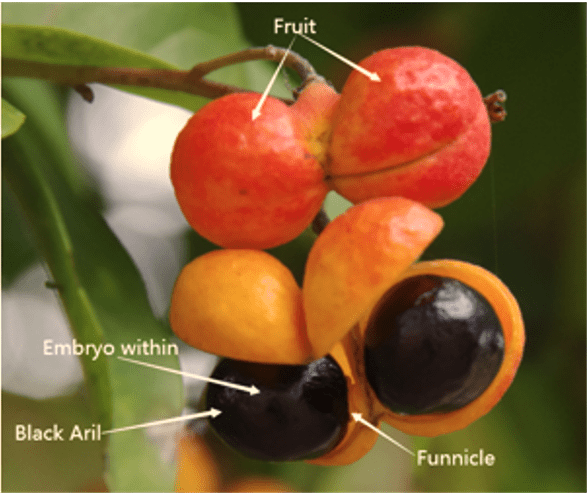

Ovules: From ovum, which is Latin for an egg. It refers to a structure that develops into a seed when fertilized. A mature ovule consists of a food tissue covered by one or two future seed coats, known as integuments. Each ovule is attached by its base to the food source while developing by means of a funiculus.

Peduncle: From pedis, which is Latin for a foot. It refers to the structure that supports the pedicels, which in turn support the inflorescences and later the fruit.

Pedicle: From pediculis, which is Latin for a little foot. It refers to the structure that supports the inflorescence and later the fruit.

Petal: From pétalon, which is Ancient Greek for a thin metallic leaf. It refers to the modified leaves that surround the reproductive organs of flowers. They are usually brightly coloured, unusually shaped or larger in order to attract pollinators.

Pistil: From pistillum, which is Latin for the female reproductive organs that are the centre of the inflorescence. It is capable of receiving pollen and producing a fruit, it is divided into an ovary, style and stigma.

Sepals: From s?palum, which is Latinized from the Ancient Greek words of s?par?tus, to seperate and pétalon for a thin metallic leaf. It refers to that part of the inflorescences usually behind the petals, when they exist. They are found on the outermost part of the flower, and like a petal, a sepal is considered to be a modified leaf and are collectively known as the calyx.

Stamen: From stêma, which is Ancient Greek or st?men, which is Latin for to have stamina or the male reproductive organs that are near the centre of the inflorescent. It is the male reproductive organs of a flower that consists of an anther and a filament.

Stigma: The stigma, stigmas or stigmata is the receptive tip of a carpel, or of several fused carpels, in the gynoecium of a flower usually found at the apex of the style which links it to the ovary.

Style: From stíz? which is Ancient Greek or stilus, which is Latin for to mark with a pointed instrument. It is the female reproductive organ that links the ovaries with the stigma in a flower.

Floral Symmetry

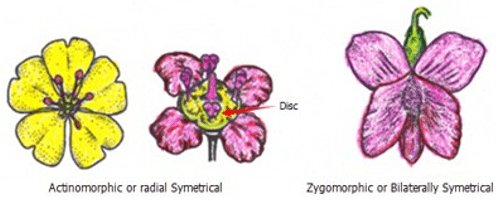

Actinomorphic: From aktís which is Ancient Greek for a ray and morph?, which is Ancient Greek for to take a shape or form of. It refers to a flower, which is capable of being divided into equal halves along any axis.

Bilaterally Symetrical: From bi, which is Latin for twoand later?lis, which is Latin for a side. It refers to a flower, which is capable of being divided into equal halves along just one axis.

Radial Symetric: From radial, which is Latin for a spoke in a wheel and symetrical, which is to have harmonious or proportionate arrangement of parts. It refers to a flower, which is capable of being divided into equal halves along any axis.

Zygomorphic: From zugón, which is Ancient Greek for a yoke and morph?, which is Ancient Greek for to take a shape or form of. It refers to a flower, which is capable of being divided into equal halves along just one axis.

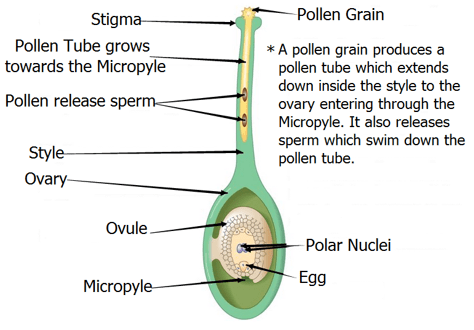

Fertilization: Is the process of sexual reproduction, which occurs after pollination and germination. Fertilization can be defined as the fusion of the male gametes (pollen later sperm) with the female gametes (ovum) to form a diploid zygote. It is a physicochemical process which occurs after the pollination of the carpel.

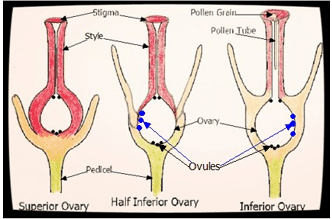

Half Superior: Is anovary, which is partially embedded or surrounded by the receptacle.It is also known as a half inferior ovary.

Half inferior: Is anovary, which is partially embedded or surrounded by the receptacle. It is also known as a half superior ovary.

Inferior: Is an ovary, which is positioned below the receptacle of a flower.

Micropyle: Is a minute opening in the integument of an ovule of a seed plant, which allows the sperm to enter for fertilization to be completed.

Ovary: From ovum, which is Latin for an egg. Is the enlarged basal portion of the pistil. That is the female organ of a flower. The ovary contains ovules, which develop into seeds upon fertilization. The ovary itself will mature into a fruit, either dry or fleshy, enclosing the seeds.

Ovules: From ovum, which is Latin for an egg. It refers to a structure that develops into a seed when fertilized. A mature ovule consists of a food tissue covered by one or two future seed coats, known as integuments. Each ovule is attached by its base to the food source while developing by means of a funiculus.

Polar Nuclei: Two nuclei that migrate to the center of the embryo sac and fuse with a male nucleus (sperm) to form the primary endosperm nucleus which divides and sometimes forms the endosperm.

Pollen: It refers to the powdery product synthesized by seed plants responsible for the production of the male gametes of the plant and contain half the meiosis required for the ovum to develop. The term pollination refers to the transfer of pollen grains from the anther to the stigma of a flower.

Pollination: Is the act of transferring pollen grains from the male anther of a flower to the female stigma. The goal of every living organism, including plants, is to create offspring for the next generation. Pollination is the exact moment the correct pollen of a species adheres to the stigma of the same species. The stigmas of flowering plants selectively recognize pollen from the same species in many ways. The physical shape of the pollen and times that the stigma is receptive and the pollen is released are recognition factors to fertilization. The physical shape is akin to the recognition between the pollen and the stigma is a geometric one. It is analogous of a lock only being locked or unlocked by the key which was designed for it. This is only part of the mechanism of recognition. Another part is through biochemical interactions, where proteins and ensymes play an important role.

Pollen Tube: A pollen tube is a tubular structure produced by the male gametophyte; pollen, of seed plants in the process following pollination. We understand they are used as a model for understanding plant cell behaviour and they exist. Presently it is not comprehendable, how the pollen tube responds to extracellular guidance signals that eventually leads to fertilization of the ovum.

Superior: Is an ovary, which is positioned above the receptacle of a flower.

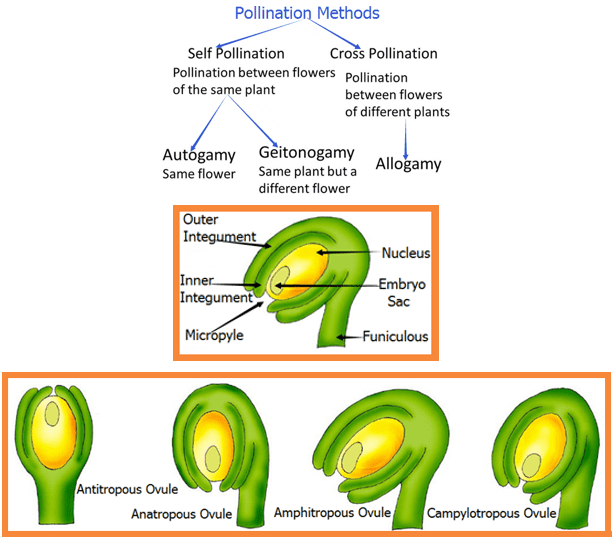

Pollination Methods

Allogamy: From állos, which is Ancient Greek for the other and gámos, which is Ancient Greek for to marry or marriage. It refers to cross-fertilization, occurs when an ovum of a flower is fertilized by the spermatozoa of another flower.

Autogamy: From auto-/autós, which are Ancient Greek for self or oneself and gámos, which is Ancient Greek for to marry. It refers to where self fertilization, occurs when an ovum of a flower is fertilized by the spermatozoa from the same flower.

Cross Pollination: Is the same as allogamy – From állos, which is Ancient Greek for the other and gámos, which is Ancient Greek for to marry or marriage. It refers to cross-fertilization, occurs when an ovum of a flower is fertilized by the spermatozoa of another flower.

Embryo sac: Is the female gametophyte of a seed plant consisting of a thin-walled sac within the nucellus that contains the egg nucleus and other nuclei which give rise to endosperm on fertilization.

Geitongamy: From geít?n, which are Ancient Greek for a neighbour and gámos, which is Ancient Greek for to marry. It refers to where self fertilization from the same plant occurs. In flowering plants, pollen is transferred from a flower to another flower on the same plant, and in animal pollinated systems this is accomplished by a pollinator visiting multiple flowers on the same plant.

Funiculous: From f?niculus, which is Latin for a thin rope or cordage. It is any cord-like structure in flowering plants, especially the funiculus, which is the stalk that attaches an ovule to the placenta. Refered as the umbilical cord in animals.

Integument: From integumentum, which is Latin for a thin covering. It refers to the natural covering of an organism or an organ, such as its skin, husk, shell, or rind. There are two thin intergumentums layers around the ovum, the outer and inner.

Mycropyle: From mikrós, which are Ancient Greek for small or tiny and púl?, which is Ancient Greek for a gate or entrance. It refers to a minute opening in the integument of an ovule of a seed plant of which the sperm must enter to complete fertilisation of the ovum.

Pollination: Is the act of transferring pollen grains from the male anther of a flower to the female stigma. The goal of every living organism, including plants, is to create offspring for the next generation. Pollination is the exact moment the correct pollen of a species adheres to the stigma of the same species. The stigmas of flowering plants selectively recognize pollen from the same species in many ways. The physical shape of the pollen and times that the stigma is receptive and the pollen is released are recognition factors to fertilization. The physical shape is akin to the recognition between the pollen and the stigma is a geometric one. It is analogous of a lock only being locked or unlocked by the key which was designed for it. This is only part of the mechanism of recognition. Another part is through biochemical interactions, where proteins and enzymes play an important role.

Self Pollination: It refers to where self fertilization, that is occurs when an ovum of a flower is fertilized by the spermatozoa from the same flower.

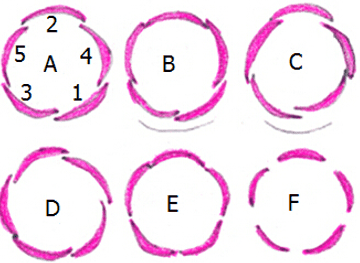

Petal Arrangements

A Quincuncial: Is to have a five-ranked arrangement of the petals or sepals of a pentamerous calyx or corolla, imbricated so that two petals are exterior, two petals are interior, and the fifth has one edge exterior and one interior.

B, C Cochleate: From cochleatus, which is Latin for a spiral or screwed form. Is to have a five-ranked arrangement of the petals or sepals of a pentamerous calyx or corolla. The lobes overlap so that lobe initiated third was innermost, overlapped by the fourth, then the fifth, the second, and lastly the first, which was always outermost. The petals may also be twisted at the same time.

D Contorted, Convoluted or imbricate: Is to have a five-ranked arrangement of the petals or sepals of a pentamerous calyx or corolla, contorted so that each petal or sepal has one margin overlapping the adjacent petal and one margin underlying the adjacent petal on the other side. Sepals likewise.

E Valvate: Is to have a five-ranked arrangement of the petals or sepals of a pentamerous calyx or corolla, valvate so that the margins of each petal or sepal are touching but so that none are overlapping or underlying the adjacent margin.

F Open: Is to have a five-ranked arrangement of the petals or sepals of a pentamerous calyx or corolla, in an open format so that the margins of each petal or sepal’s margins have a clear space between the margins

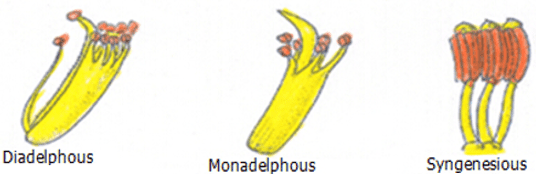

Stamen Layout

Stamen Position

Gynandrous: Is where the stamens are attached to the ovary or pistil.

Stamen Fusion

Diadelphous: From di, which are Ancient Greek for two and adelphós, which is Ancient Greek for a brother. It refers to how the filaments are fused together or partly by the filaments so that they form two separate bundles, or single bundle with a lone stamen.

Monodelphous: From mono, which are Ancient Greek for one or a single and adelphós, which is Ancient Greek for a brother. It refers to how the filaments are fused together to form a tube.

Syngenesious: From sún, which is Ancient Greek for with, in company with or together with, and génesis, which is Ancient Greek for to originate from. It refers to how the filaments are free but the anthers are fused together.

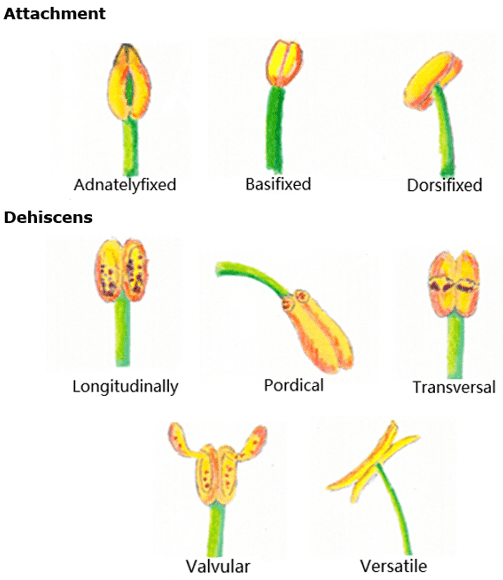

Anther Attachment & Dehiscence

Adnately fixed: It refers to anthers, which grow together and are joined to the filament lengthwise.

Basifixed: It refers to anthers, which are joined to the filament at their base.

Dorsifixed: It refers to anthers, which are joined to the filament at the centre of back.

Longitudinally: From longitudo, which is Latin for a length. It refers to anthers, which dehisc lengthwise.

Pordical: It refers to anthers, which dehisc through pores at their apex.

Transversal: It refers to anthers, which dehisc through horizontal slots midway between the base and apex.

Valvular: It refers to anthers, which dehisc with a portion of the pericarp fragmenting or peeling backwards at maturity.

Versatile: Refers to anthers, which are dorsifixed thus enabling them to dehisce by splitting longitudinally along a single line and swing freely.

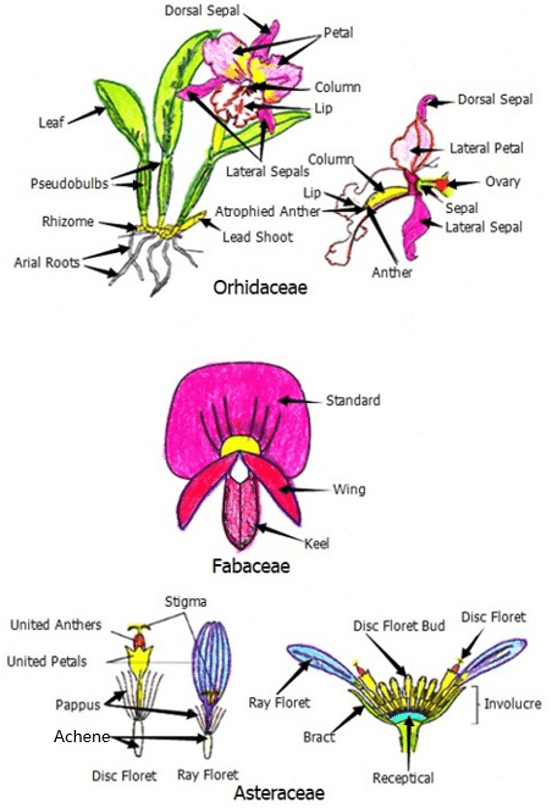

Special flower forms Orchids, Fabaceae & Asteraceae

Orcidaceae: From órkhis, which is Ancient Greek or orchis, which is Latin for testicles. It refers to the appearance of many pseudobulbs resembling a man’s testicles.

Arial roots: It refers to roots, which grow on the above-ground parts of a plant. Aerial roots on woody vines function as anchors, affixing the plant to supporting structures such as rocks, and trunks. Some types of aerial roots also absorb moisture and nutrients, similar to underground roots.

Atrophied Anther: From atrophía, which is Ancient Greek for to waste away. It refers to the diminution, a reduction in size or a reduction in the importance of or decline or loss of a function.

Column: The column, or the gynostemium, is a reproductive structure that can be found in several plant families like Aristolochiaceae, Orchidaceae, and Stylidiaceae. It is derived from the fusion of both male stamens and female pistils into a single organ.

Dorsal sepal: It refers to the apparently upper sepal of a flower; in the majority of orchids this is actually the lower sepal because the flowers are resupinate.

Pseudobulbs: From pseud?s, which is Ancient Greek for false, not genuine or lying and bolbós, which is Ancient Greek or bulbus, which is Latin for the part of a plant with round swellings on underground stem. It refers to is a storage organ found in many epiphytic and terrestrial orchids. Pseudobulbs form from a single internode produce the leaves and inflorescence from the top, while those that are formed from several internodes can possess leaves along its length.

Rhizomes: From rhíza, which is Ancient Greek for a root. It refers to a modified subterranean plant stem that sends out roots and shoots from its nodes and has the ability to store starch.

Fabaceae: From faba, which is Latin for a bean and aceae, which is Latin for a family. It refers to plants with compound leaves, the production of fruits known as legumes and often have nitrogen fixing bacteria attached to their roots.

Keel: Isa ridge resembling the keel of a boat. It refers to where the lateral petals of legumes fuse together in a flower where the reproductive organs are.

Standard: It refers to the larges adaxial petal in the flower of Papilionaceae along with the two wing or lateral petals and the two keel petals.

Wing: It refers to the two lateral petals in the flower of Papilionaceae along with the standard and the two keel petals.

Asteraceae: From ast?r, which is Ancient Greek for a star and aceae, which is Latin for a family. It refers to plants in the daisy, or composite family of the flowering-plants.

Achene: It refers to one-seeded fruits lacking special seams that split to release the seed. The seed coat is attached to the thin, dry ovary wall (husk) by a short stalk, so that the seed is easily freed from the husk.

Bract: Is a modified leaf or scale, usually small with a flower or flower cluster in its axil. Bracts are sometimes larger and more brightly coloured than the petals.

Disc Floret: Refers to any of the small tubular flowers at the centre of the flower head of certain compositaeae plants.

Involucre: Is a ring of small leaves or bracts found at the base of a flower, flower cluster, or fruit in all plants of the compositaceae family.

Pappus: It refers to the tuft of hairs on the seeds of many plants, which assists in the dispersal of the seeds by the wind.

Ray Floret: Is the small flowers with a flat, strap shaped, colourful petal usually occupying the peripheral ring/s of a composite flower.

Receptical: It refers to composite flowers, which have the individual flowers or florets being born a swollen flattened or convex base known as the receptacle.

Resupinate: From resupination, which is Latin for bent back with the face upward or on one’s back. It refers to being being upside-down or facing upward.

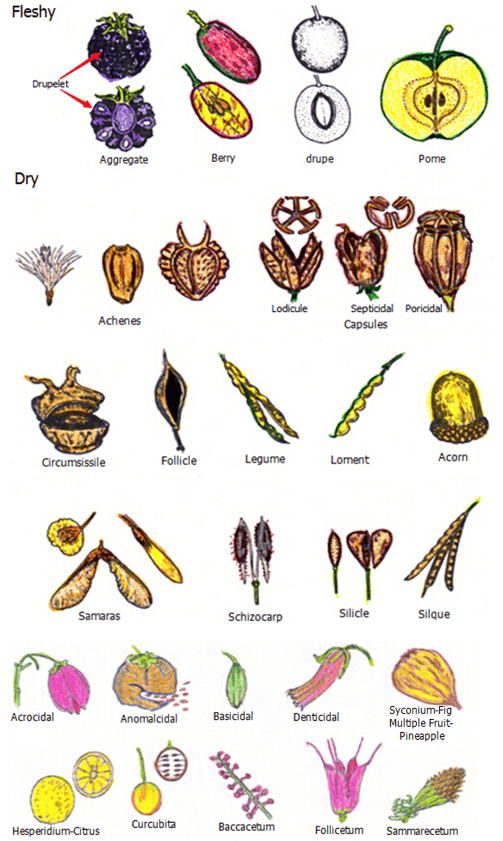

Types of Fruit

Academy of science.

Aggregate: It refers to composite flowers, which have the individual disc florets and ray florets being born a swollen flattened or curved base.

Berry: Is a fleshy fruit without a stone that are produced from a single flower containing single ovary. The boundary between a drupe and berry are often conflicting.

Drupe: Is an indehiscent fruit in which the outer fleshy part; exocarp, or skin, and mesocarp, or flesh, surrounds a single shell; the pit, stone, or pyrene, of hardened endocarp with a seed or kernel inside. These fruits usually develop from a single carpel, and mostly from flowers with superior ovaries. The boundary between a drupe and berry are often conflicting.

Druplet: Is a little drupe, which is located in an individual fruit within an aggregate.

Pome: From p?mum, which is Latin for a fruit. It is a type of fruit produced by flowering plants in the subtribe Malinae of the family Rosaceae.

Achene: It refers to one-seeded fruit lacking special seams that split to release the seed. The seed coat is attached to the thin, dry ovary wall (husk) by a short stalk, so that the seed is easily freed from the husk.

Acorn: Is the fruit of an oak tree, consisting of a smooth thick-walled nut in a woody scaly cuplike base. Often referred to in many nuts being acorns.

Baccacetum: Is a semi fleshy fruit without a stone that are produced from a single flower containing single ovary. The boundary between a baccatum and berry are often conflicting. A good example of a baccatum fruit are found in chillis where there is a thick exocarp and mesocarp while the endocarp is missing making the fruits hollow. The placenta is usually dry and well pronounced.

Capsules: Is a type of simple, dry or rarely semi-fleshy dehiscent fruit produced by many species of angiosperms –

* Acrocidal: Is a dry fruit which dehisces by slits at the apex.

* Anomalcidal: It refers to a capsule, which dehisces at maturity through a horizontal slit or fissure.

* Basicidal: It refers to a longitudinal capsule, which dehisces at maturity through slits or fissures that start at the base and extend longitudinally to the apex.

* Denticidal: It refers to a longitudinal capsule, which dehisces at maturity through slits or fissures that start at the base and extend longitudinally to the clefts near the apex.

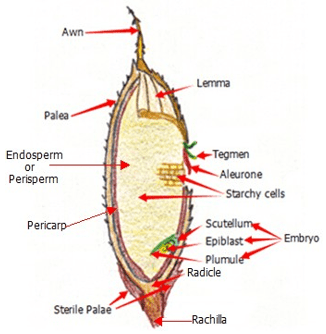

* Lodicule: From l?d?cula, which is Latin for a small blanket. It refers to a structure that consists of between one and three small scales at the base of the ovary in a grass flower that represent the corolla. It is thought to be a rudimentary perianth. The swelling of the lodicules forces apart the outer shells exposing the seeds.

* Poricidal: It refers to capsules, which dehisc through pores at or near to their apexes.

* Septicidal: From s?ptum, which is Latin for an enclosure, wall or fence. It refers to capsules, which in the fruits dehisce longitudinally along the septum.