This topic has been debated and is best left to the following organizations to place a definition in place. Often very heated debates become emotional and not constructive. As can be seen their definitions are fair to both Humans and wildlife.

Human–wildlife conflict is defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) as “Any interaction between humans and wildlife that results in negative impacts on human social, economic or cultural life, on the conservation of wildlife populations, or on the environment.”

The Creating Co-existence workshop at the 5th Annual World Parks Congress held between the 8th and 17th of September 2003 in Montreal defined human-wildlife conflict in the context of human goals and animal needs as, “Human-wildlife conflict occurs when the needs and behavior of wildlife impact negatively on the goals of humans or when the goals of humans negatively impact the needs of wildlife.”

A 2007 a review by the United States Geological survey defined human-wildlife conflict in two contexts; firstly, “Actions by wildlife conflict with human goals, i.e. life, livelihood and life-style, and, secondly, human activities threaten the safety and survival of wildlife.” However, in both cases, outcomes are decided by human responses to the benefit of a few humans and the demise of the wildlife concerned.

The Government of Yukon defines human-wildlife conflict simply, but through the lens of damage to property, i.e. “Any interaction between wildlife and humans which causes harm, whether it’s to the human, the wild animal, or property…….” Here, property includes buildings, equipment and camps, livestock and pets, but does not include crops, fields or fences.

Human–wildlife conflict occurs with various negative results for nature as it is always about me the human being and very little about the affects on them the plants and animals. Too often we hear the cries of kill the shark, the snake or the crocodile because it killed a human. But what about trees do they kill? They have no where to hide no where to turn to yet they too are falling prey to human conflict.

As a result we often displace the very organisms that are essential to our very existence, then turn and gloat about what we have “built and achieved” never mentioning what we have “displaced, supplanted, maimed, killed, annihilated or oblitered,” to build the personal monument of fame and profit. The major outcomes of human-wildlife conflict usually always end in the same manner without consideration of what is progressively happening. Those outcomes can be outlined as follows:

* Increased injury and loss of life of humans and wildlife,

* Increased crop damage, livestock depredation, predation of managed wildlife stock,

* Increased damage to human property,

* Increased imbalances can occur due to the trophic cascade affect,

* Increased destruction of habitat,

* Increased collapse of wildlife populations and reduction of their geographic ranges.

Trophic cascade- Is where the predator determines the traits of a herbivore or a herbivore determines the traits of a plant. That is to say if the caterpillars ate a thistle and they preferred to eat the thistles with the white flowers the thistle would eventually end up with only coloured flowers. But if the birds mainly fed on the caterpillars that consumed the white flowers then the white flowers may take over as the only moths left would be those eating the purple flowers. (See chapter 28 plant – Microbe and Insect Interaction for more details on Trophic cascade.)

Past management techniques of wildlife are of two types. The first type is the traditional techniques which aim to stop, reduce or minimize conflict by controlling animal populations in different ways and always ends up the animals and plants coming off second best.

Lethal control has the longest history but has major drawbacks. It is often controversial, expensive to administer and often has minimal affect with changing natures cunningness against humans as those that do survive understand better the methods employed to kill them.

Another measure rests with trans location, regulation and preservation of animal populations. This often had the affect of creating stress on the animal trapped and being relocated as well as placing greater pressures on the existing population in the located area.

Modern methods depend upon the understanding of ecological and ethological understanding of the wildlife and its environment to prevent or minimize conflict. (Refer to Chapter 26 Urban Landscapes)

Potential solutions to these conflicts include electric fencing, land use planning, community-based natural resource management (CBNRM), compensation, payment for environmental services, ecotourism, wildlife friendly products, or other field solutions

I took the basic format and ideas for the following article adapting it to the Australian scene and situation from http://www.docin.com/p-298330264.htm

The management of Human Conflict Management (HWC) is based on strong integrated community values and the development of manageable plans for wildlife. Such practices must stem from the very people who are displacing the wildlife as both people and wildlife suffer enormously as a consequence of past uncontrolled greedy human development.

HWC is a growing worldwide problem that manifests a multifaceted range of excuses from being:

* Too expensive,

* Too difficult to resolve,

* Underprivileged domains are not considered,

* The divisiveness of extent of the problem and solutions

* Rural communities feel under represented yet are expected to foot the major the expenses and give the greatest attention

It is for these reasons that a better understanding with better management plans and implementation needs to be created and adopted by the whole community.

Humans are encroaching on environments and wilderness regions all over the world at an ever rapid rate which is having devastating consequences causing the extinction and vulnerability of many animals and plants to survive. Those animals and plants which are most exposed to the human conflicts are those that are most threatened to extinction.

HWC also undermine human welfare, health and safety, and have economic and social costs well beyond what is physically measurable. Nuisance encounters with small animals, exposure to zoonotic diseases, physical injury or even death caused by larger or venomous predator attacks have high financial costs for individuals and society in the form of medical treatments to cure and prevent infections transmitted from animals.

Humans can be economically affected through destruction and damage to property and infrastructure like vehicle accidents with kangaroos and wombats. Negative social impacts include absenteeism from school or work, additional labor/insurance costs, loss of sleep, fear and phobias.

Such broad environmental, human health and safety, economic and social impacts suggest that governments, wildlife managers, scientists and local communities need to understand and recognize the problem and adopt measures to resolve or at least curb them in the interest of human and environmental well being.

Driving forces and global trends have contributed to the escalation of HWC worldwide and can be grouped into:

* Human population growth:

Demographic and social changes place more people in direct contact with wildlife. As result of human population growth, settlements expand into and around protected areas as well as in urban and suburban areas encroaching into wildlife habitats especially wildlife corridors (Outer perimeters of most towns and cities – Western Sydney), restricting species into marginal habitats and direct competition with local communities. The greatest numbers of conflicts arise; not in restricted nature reserves or even rural areas, but in urban conglomerates.

* Land use and land transformation:

The greatest areas of sudden conflicts arise from land use transformation where whole forests, grassy woodlands and other ecosystems are transformed into agrarian areas or urban satellite cities overnight as a consequence of the increasing demand for food production, energy and raw materials. (The Murrumbigee Cotton scheme and the Ord River Scheme.)

Conflict is intensified by land use fragmentation and the development of small scale farming placing the surrounding forests under greafter stress. (Corindi Blue Berry Farms)

Species habitat loss can be viewed as degradation and fragmentation of prime wildlife stands that are also interconnected with population growth and demand. (Logging parcels in Tasmanian virgin forests.)

* Species habitat loss:

The greatest areas of sudden conflicts arise from land use transformation where whole forests, grassy woodlands and other ecosystems are transformed into agrarian areas or urban satellite cities overnight as a consequence of the increasing demand for food production, energy and raw materials. (The Murrumbigee Cotton scheme and the Ord River Scheme.)

Conflict is intensified by land use fragmentation and the development of small scale farming placing the surrounding forests under greafter stress. (Corindi Blue Berry Farms)

* Degradation and fragmentation of previously suitable habitats:

Specie’s habitat loss can be viewed as degradation and fragmentation of prime wildlife stands that are also interconnected with population growth and demand. (Logging parcels in Tasmanian virgin forests.)

Degradation of virgin wildlife reserves from g rowing interest in ecotourism and increasing access to nature reserves. (Sections of the Great Barrier Reef) Recreational activities and growing public interest in charismatic species, such as large carnivores like the salt water crocodile and endangered species like Mastchie’s Tree Possum place the surrounding lands under greater preasure resulting in the need to adequately monitor and regulate public access and large-scale use of protected areas.

* Growing interest in ecotourism with a consequent increase in access to nature reserves:

The tourist industry is totally aware of the consequences it faces as a result of the loss of wildlife or the gain in National Parks occurs in their area. (Wild Rivers in south Western Tasmania’s Wilderness area was reborn following the declaration and a abandonment of the Damming of the Franklin in Tasmania.)

* Increasing livestock populations competitively excludes local indigenous herbivores:

Wild camels and Water buffalo have effectively decreased and [laced several plants and animals on the vulnerable and endangered list. (The Tamar Wallaby)

* An abundance and distribution of wild prey:

When native prey is abundant, wild predators consume it in

preference to consuming livestock as impoverishment of prey populations is one of the major causes of carnivores shifting their diets to livestock. Clearly, this is due to the ease of capture and limited escape abilities of livestock that are bred for meat or wool becoming slow and cumbersome in movement to conserve energy.

Dingoes have been displaced by feral dogs and cats which also compete with the quolls. Wedge tailed Eagle preying on weak lambs in times of drought and famine. A similar experience is seen during stress periods amongst fruit grazing bats and birds which seek out fruits like apples and citrus. (Rainbow Lorikeets – Trichoglossus haematodus haematodus)

* Increasing native wildlife populations of those species that are able to withstand HWC as a result of better conservation programs:

The growth in numbers of the 3 the largest kangaroos have provided more food for wild dogs exasperating an already major problem. (Refer to article on Kangaroos below)

* Changing climatic factors:

This is an on going problem already dealt with under several different chapters.

* Stochastic events and movements compared to the present situation:

The explosion or decrease in actual numbers of specie varies throughout the year based on many factors relating to survival. These figures are difficult to extrapolate as there are many seasonal variations contribute to what is normal and what is actually happening. While the Helmeted Honeyeater’s (Lichenostomus melanops cassidix) population increases every spring it declines over the year due to predatation and environmental factors.

* Human population growth:

Refer to chapter 19 as it was dealt with extensively there.

* Alteration of food Chains:

The alteration of natural food chains along with water availability can completely change ecosystems overnight to decades. The Ord River dam once filled, extensively changed both the micro and macro climates in the creeks and rivers as well as the surrounding countryside. According to Claudia Bertorello-Kell 2007 the Fresh Water Crocodile, Crocodylis johnsonii is estimated to number 25,000 where it once probably numbered a few hundred. Its food source has obviously increased proportionately.

Most of the species scientists are concerned over are carnivores and large home range species which play an important role from a conservation stand point as they have a profound influence on biological communities from the prime producer to the top of the food chain. The disappearance or explosion in numbers in a given area often alters the structure and function of entire ecosystem and neighbouring ecosystems through specific competition and regulation of prey population density in their ecosystem.

Magpies

Suburbia in a Flap as some residents want the magpies permanently relocated despite the birds being very territorial and the relocated birds will succumb to the resident family. For a few short weeks during breeding they entertain us for the remainder of the year with their melodious trills. – andi Mellis

The Australian magpies are the cause of major wildlife management conflict in many suburban areas throughout Australia. Mitigation of this conflict is becoming increasingly difficult in some locations because of community opposition to the destruction of the birds involved, which remains a common management solution of many wildlife agencies.

Translocation trapping and releasing the birds elsewhere has had limited success. The offending birds are never seriously evaluated to see whether they have survived, caused stress and pressure on the new community which it has been released into or the existing territory and birds from which it came.

Male magpies that have been captured and released at distances less than 30km away returned quickly to their original territory. Male magpies that have been captured and released at distances more than 30km away have never been seen again.

New males are known to replace the captured birds within days of them disappearing. There appears to be no negative behaviour, or interactions between new males and the resident females or her chicks.

Kangaroos

Australia’s problem with abundant kangaroo species

Australia has about 50 species of marsupial mammals of the Super family Macropodoidea. Most of them have declined and are still in decline ever since Europeans settled here. Some are at the point of extinction while others have already met that fate. Some like the grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus) and red kangaroo (Macropus rufus) have thrived amid the clearing and extra watering holes to the extent that they are now among the most abundant large mammals anywhere in the world. The abundant species, particularly the three largest species of kangaroo, are so numerous in many rural areas that they are regarded as pests.

Missy, Macropus rufogriseus lower & right relaxing in the safety of our garden & computer room where no cats or dogs prevailed. We changed her name to “Chocolate thief” when she comes inside to steel our chocolates. She adopted us during the 2019 drought when she just entered the house and begged for food. We obliged and now have a permanent guest. – andi Mellis

The sheer number of kangaroos, with their high conservation status, and the recognition that they are regarded as a serious pest by graziers gives Australian conservation agencies a problem. Not surprisingly, all Australian macropods are protected by law, as is all of Australia’s wildlife. The solution to this conflict in the past has been to issue limited seasonal permits which allow kangaroos and some of the most numerous wallabies to be shot as pests. Most of the control though is affected through commercial harvest of kangaroos and wallabies for meat and for leather.

Commercial harvesting of native animals even as pest destruction of wildlife is controversial in Australia. When the subjects are as appealing and as well known as Australia’s fauna emblem, kangaroos attract even more attention. Kangaroos are the most readily identified symbol of Australia, and that they are harvested by shooting, only exacerbates the situation and contributes to organized public campaigns against their commercial use. This is despite it being the only method to commercially farm and have the animals taken to market.

Kangaroo management in Australia comes under close scrutiny, both locally and internationally and there has been significant public debate about the issues which kangaroo harvesting raises. A valuable outcome of this public scrutiny and debate has been that all levels of government and political parties in Australia have given very close attention to the philosophy behind and the operational aspects of kangaroo farming, including research and monitoring. Striving for world’s best practices and public accountability is essential to ensure the long term operation of farming kangaroos. As a result it is important and necessary to ensure continuation of self reproduction of kangaroo populations remain static for those species that are required for food and leather and those species that are threatened are preserved with their ecosystems remaining intact.

Environmental arguments are nearly always based upon an individual’s moral judgments and cannot be debated logically. Animal welfare is becoming an increasing concern within society. Wild harvesting will always involve some injuries and protracted deaths but provided it is kept to a minimum and accounted for there should not be a problem. This must be weighed up against reduction in other forms of killing like when an animal changes status from a pest to a resource, the quality of life for individuals in dense, unharvested populations during droughts and stress on alternative land uses and stress on the land from over grazing if harvesting is not allowed.

Australia’s kangaroo harvesting programs

The following article has been adapted to the chapter because of its relevance and importance in conveying the real position of Kangaroo harvesting in Australia. References have been kept in place of those who carried out the work and had it reported.

Personally I would like to see a position where farmers were given property quotas to maintain. That is if the farmer increased the numbers over a certain figure he would be allowed to commercially send the excess numbers to market or transfer them to other farmers similar to cattle and water. This would allow far better control of numbers while at the same time would be far less expensive to maintain in the long term. This would also ensure the species future and quell the emotional issues that surround present culling programs during plagues. When the numbers increase above or decrease below a certain number the farmers would be allowed to trade excess stock and run the kangaroos in a similar manner to a station.

Seven species of macropod are currently the subject of Management Programs that have been approved to allow export with all these species having larger populations now than when British settlement started and all the animals have healthy populations:

Red kangaroo (Macropus rufus), Qld, NSW, SA, WA

Eastern grey kangaroo (M. giganteus), Qld, NSW

Western grey kangaroo (M. fuliginosus), NSW, SA, WA

These first three species are the most abundant and make up over 95mm of the commercial harvest.

Common wallaroo or euro (Macropus robustus), Qld, NSW, SA, WA

Whiptail wallaby (M. parryi), Qld

Bennetts wallaby (M. rufogriseus), Flinders Island Tas

Tasmanian pademelon (Thylogale billardierii), Flinders Island Tas

Starting in 1998 the harvest of Bennetts wallabies and Tasmanian pademelons from Flinders Island have been approved for export. Additional harvesting of some of the abundant wallaby species occur in the rest of Tasmania but are not exported.

Apart from the above figures the document only deals with the commercial harvest of macropods from the mainland Australia.

Under Australian Law, the individual States have responsibility for wildlife management within their state boundaries, whereas the export of all wildlife or wildlife products is controlled under the provisions of the Wildlife Protection (Regulation of Imports and Exports) Act 1982 (WP (REI) Act) with Environment Australia administering the Act and giving advice to the relevant Federal Minister. The Assistant Secretary of Wildlife Australia is the Designated Authority under the WP (REI) Act and has an intermediary role in the process of approval of the State Kangaroo Management Programs, providing advice to the Minister because, under agreement reached at ANZECC (Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council), State programs become part of an overall National Plan of Management for kangaroos. The Federal Minister takes advice also from the Scientific Committee for Sustainable Use of Wildlife. For more details.

In practice, these requirements and procedures mean that each of the relevant States (Qld, NSW, SA and WA) develops a Kangaroo Management Program which is subject to review by Environment Australia, in consultation with the Minister’s Committee for Sustainable Use, before going to the Minister for his consideration and approval. Approval of a Program may be given for up to five years. Management Programs provide statements of the aims of kangaroo management in the State, usually to ensure the conservation of the species throughout their ranges and, by conducting an annual harvest, to address grazier’s concerns about kangaroos causing lost revenue or inhibiting land regeneration. Increasingly, States are including in the aims the additional goal of treating the kangaroos as a renewable resource. The Programs also provide details of annual population monitoring, how annual quotas are derived and used to limit harvesting, procedures such as the issue of tags by which harvests are regulated and, indeed, all aspects of the operation and regulation of kangaroo management in that State.

Management Programs requiring renewal or variation are submitted to Environment Australia after which they are available for a period of one month for public comment. Harvest quotas are submitted on an annual basis.

The quota proposals, based on population trends and the most recent survey data, are considered by the same processes which lead to the approval of Management Programs, and recommended to the Minister for signing early in December. It is comparatively common for clarifications or modifications to be made to both management programs and quota proposals following the committee stage.

In recent years, quotas to all States have typically totalled about four million kangaroos. The total annual harvest has not yet reached that limit, although the proportion of the national quota taken has increased recently. Details of quotas and harvests, species by species in each State for the last few years, along with population trends, are provided .

The extent to which the annual harvests have been successful at reducing kangaroo numbers is controversial, with people in the rural industries usually being dissatisfied that kangaroos remain so numerous, despite the large harvests. In practice, the quotas in recent years have been set within the capacity of the kangaroo populations to compensate. That is, the harvest quotas have been set primarily with sustainability in mind. The argument concerns the extent to which the subsequent harvest provides damage mitigation.

That is not to say, however, that kangaroo populations are not diminished as a result of the harvests, although that is often the assumption made by graziers in the face of continuing high numbers. There are good reasons for accepting that the full taking of the quota, typically 15mm of the estimated populations, would lower kangaroo numbers by approximately 40mm compared to what the numbers would be if there were no harvesting. Actual harvests in recent years would have gone a good way towards that. There is a view often expressed that quotas should be raised further, to achieve more effective pest control. This is countered by a different view, which questions the extent to which further reduction in kangaroo numbers really would lead to increased sheep productivity. The whole area is under active discussion among scientists and land managers, and the issues will be reviewed.

While the harvesting of kangaroos is in some States undertaken primarily for pest control, to mitigate damage to crops, pasture and fences, there is increasing recognition that kangaroos are a valuable resource whose commercial use is in tune with ideas about gaining conservation benefit from the sustainable use of wildlife.

On the other hand the tree kangaroos is habitat loss. Destruction of rainforests means loss of habitat, and loss of food source. Unlike some other highly adaptable marsupials, tree kangaroos need a very specific habitat. Also, in parts of northern Australia, quite a few tree kangaroo deaths are caused by cars. Introduced species such as foxes and wild dogs are also a major problem.

It should be noted that not all species of tree kangaroos are endangered.

One Australian species is listed as endangered, and that is the Lumholtz’s Tree kangaroo.

Crocodiles

From Resource to Endangered and Back to

Controlled Resource

Saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) in the Northern Territory of Australia were protected in 1971, after a severe population decline resulting from 26 years of intense commercial hunting. By that time wild saltwater crocodiles were rarely sighted anywhere and they were commercially extinct in areas where they had once been abundant. Standardized monitoring by spotlight surveys started in 1975 and provided relative density indices over time (1975-2009) as a unique record of the post protection recovery of wild crocodilian populations.

Saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) have a terrifying reputation only because we enter their territory on their terms. – andi Mellis

We examined the survey data for populations at 12 major tidal rivers, individually and as a single subpopulation. The pattern of recovery in the subpopulation in both abundance and biomass was approximated by logistic curves, predicting 5.26 non hatchling crocodiles weighing 387.64 kg sighted per kilometer of river in 2010. We predicted potential carrying capacity as 5.58 non-hatchling crocodiles (5.73mm higher than 2010) weighing 519.0 kg (25.31mm higher than 2010). Individual rivers showed largely different abundance and biomass among rivers. The statistical model that best described the recovery in individual rivers was not always logistic. However, where it was logistic, expected carrying capacity of different rivers showed considerable variation in abundance and biomass. The variation indicates different habitat quality among the rivers. Recovery occurred despite various consumptive uses, particularly a widespread egg harvest program, which has been an integral part of the incentive driven conservation program for saltwater crocodiles in the Northern Territory since 1983.

We suggest that the saltwater crocodile population of the Northern Territory is achieving full recovery from the uncontrolled hunting in 1945-1971. Although saltwater crocodiles are considered an important natural resource, their increase in number, size, and distribution is posing management issues for public safety. Continuation of human crocodile conflict management still requires public education. (2011 – The Wildlife Society.)

The strategic removal of problem crocodiles with relocation away from settlements or placed in Australian Wildlife Parks will need to be continued, especially in areas where human settlement is beginning to encroach on crocodile habitats.

Ms Bennett grand daughter was killed by a crocodile. She told reporters that she had wanted the beasts culled after the traumatic death of her 11-year-old grand-daughter Briony Goodsell, who was taken at Black Jungle Swamp, in rural Darwin, in 2009.

“This knowledge about crocodiles has made a huge difference for our family. I feel the opposite now, like the hate has turned to a passion,” she said.

“I applied for the show … I’m not one to back away from a challenge but it was a real conflict of feelings.

“I think people need to respect crocodiles’ territory.

“Their strength is something to awe.”

Crocodiles are awesome but treated with respect and know their territory, survival with great photographs and fun is assured for all. The present polices are working well, with their numbers now reaching sustainability. All it took was management, farming, tourism and public awareness to bring a great asset back from vulnerability.

Sharks

People love Em or hate Em

On a risk valuation of death, being bitten or injured from the various types of fauna in Australia sharks pose the smallest risk behind mosquitoes, dogs, ticks, snakes, spiders, jellyfish and crocodiles yet more people are exposed to sharks than any of the other organisms found in the country. In Australia less than one person is killed by sharks on an annual basis yet it is the gruesomeness of the occasion like crocodiles that gains the media’s adverse attention followed up with the public’s ill conceived and unwarranted wrath in calling for bloodletting control. Personally I respect their majestic calmness in swimming.

The ocean is their domain. They are king of the seas, so let it be. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202109/1234710.shtml

As an ecologist before we can resolve the problems with animals we must first understand the background conflicts and misconceptions that surround sharks. Understanding the drivers of conflict and understanding the animal’s behaviors in relation to their environment, where the two environments meet or overlap (theirs and ours) and what is driving them into ours is necessary. That requires translating science into a wildlife management policy, then to try to find solutions to solve the unavoidable conflicts between humans and wild species.

The increasing numbers of human shark conflict is rising and is adversely affecting the lives and livelihoods of fisherman, swimmers and surfers as well as the sharks.

Science and management are usually reactionary to the public’s unreasonable calls for indiscriminate culling and slaughter of the animals. Surfers are generally more accepting of the slight dangers of sharks and commit themselves to providing information to park managers and scientists to resolve the conflicts between fishermen and swimmers.

With the appropriate data to make informed decisions and to their credit they, together with dedicated teams of public representatives, can deliver thriving populations along the coast away from populated areas.

Another challenge with sharks now appears to be Global Warming. As ocean temperatures warm food fish are seeking cooler waters further south and closer to the coast. This in return is also driving the sharks further south and closer to the coast in search of food which brings them into greater contact with humans as the more populated areas along with better surfing beaches are further south.

Early detection using ‘shark spotters’ serves to reduce the spatial overlap between many species of sharks including the white pointer, Carcharodon carcharias and recreational beach users during the summer months when the sharks also move further south and closer inshore.

Good research into shark migration patterns with behavioural habits coupled with shark nets and drum lines are far better alternatives to indiscriminate culling.

Swimmers, waders and surfers can assess the relative risks, based on a series of flags and sirens that alert them to current shark presence and refrain from entering the water when sharks are present. If people choose to swim when the risks are more noticeably higher then they make a conscious decision. As the risks of an incident are so low some 99.99 percent of people feel like that it is the right one.

Exclusion nets versus the culling nets which are extensively used throughout much of Australia are cost affective and offer teenagers to retirees and families a fun day at the beach with no threat of an encounter with sharks.

These simple, cost effective solutions provide both sharks and humans to coexist in close proximity in the shark’s domain.

Flying foxes

The black flying fox is not listed as threatened nevertheless, the species is exposed to several threats, including loss of foraging and roosting habitat, and mass die offs caused by extreme temperature events. When present in urban environments, black flying foxes are sometimes perceived as a nuisance. Because of their roosting and foraging habits flying fox generally bring the species into conflict with humans. It suffers from direct killing of animals in orchards and harassment and destruction of their roosts.

The black flying fox, Pteropus alecto, are being forced to enter orchards, back yards in search of dwindling food supplies caused by we humans. – andi Mellis

The black flying fox, Pteropus alecto, roosting with the red head flying fox, Pteropus scapulatus. If they can live in harmony why can’t we? – andi Mellis

I have dealt with the problems of flying foxes and solutions elsewhere so will concentrate on the zoonotic disease aspects of the animals here.( See chapter 25.)

To add to the negativity of public perception of the species, the discovery of three recently emerged zoonotic viruses that are potentially fatal to humans has intensified the hatred. The diseases include Australian Bat Lyssavirus, Hendra virus, and Menangle virus. However, only Australian Bat lyssavirus is known from two isolated cases to be directly transmissible from bats to humans.

The two direct cases involved close contact where fluids from the bats passed directly to humans via human saliva or blood. As for the other cases and the horses all of which were isolated cases indicates the disease is widespread and probably contracted through direct contact of saliva, seamen or orgasmic fluids, urine or blood.

As the animals are social and not aggressive to the point of conflict which inflicts body injuries and bleeding it would leave saliva, seamen or urine. As the disease appears to have spread rapidly seamen and orgasmic fluids can also be ruled out.

Further as the disease appears to be wide spread and in the case of Hendra Virus and Lyssavirus being previously restricted to bandicoots it is possible to make several a few limited hypothesis on the spread and why the disease has not been reported in the past in humans or horses.

Here I hypothesize that the above diseases which have all been recently discovered in bat colonies originated elsewhere and have been transmitted to the bats via a common vector or a number of vectors.

Hendra Virus and Lyssavirus most likely had a common vector to transmit the disease. On geographic evidence to date all the outbreaks reported have occurred within 40 kilometres from the east coast shoreline. As the bats are wide spread across the northern third of Australia and down the east coast why then hasn’t the disease followed the bats across the top end or further west than 40 kilometres from the coast? I did not accept all the hoo ha over Fruit flying foxes directly transmitting the diseases to horses despite the terrains of horses, humans and flying foxes overlapping.

In the north where the disease appears to be more prevalent and with deforestation the flying foxes are changing their diets moving closer to the ground where food is more prevalent after clearing and where there is less competition at the present time due to the eradication of many species due to the clearing.

Secondly in the south where the land has been cleared orchards have been established forcing the flying foxes which normally feed higher up to come closer to the ground.

Enter the vector; paralysis tick Ixodes holocyclus, which is a vector for transmiting Hendra Virus and Lyssavirus amongst Bandicoots. Haemaphysalis longicornis is also suspected as being a vector in the transmission of Hendra Virus and Lyssavirus amongst Bandicoots. Bandicoots are generally solitary animals and nearly always have 2 to 6 ticks on them. Bandicoots are the hosts to both the Ixodes holocyclus and Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks which now become prime suspects.

Now with the flying foxes eating closer to the ground they are now more likely to become a host for the ticks as the ticks which normally stay close to the ground; 1 to 2 meters, have both been recorded at up to 4 meters. Both the wild tobacco Solamum erianthum and the orchard trees especially peaches and blue berries all grow less than 4 meters. I have observed flying foxes feeding off the fruits so our prime suspects are now looking very guilty indeed.

The last piece of my hypothesis is that the tick Ixodes holocyclus geographical range is basically within 40 kilometers from the coast where as the geographical range for Haemaphysalis longicornis extends much further inland and across much of the northern part of Australia.

Here I hypothesize that the above diseases which have all been recently discovered in bat colonies and originated elsewhere namely the bandicoot have been transmitted to the bats via a common vector namely Ixodes holocyclus.

It must be further noted as the viruses move from the bandicoots to ticks and possibly horses or humans there has been no deaths or sickness from direct transmissions. There have been two fatal occurrences in humans and over 16 recorded fatalities amongst horses. The diseases that cause the fatalities are believed to be contracted via flying foxes as research and news reports have quoted.

Then I can hypothesize further that the diseases are:

* Transmuting themselves in the flying foxes into a lethal strain for horses and human,

* Transmuting themselves into a strain that can be transmitted to horses and humans that was not possible directly prior to the transmission to horses and humans via the flying foxes.

Wildlife rescue

Flying foxes often come to the attention of Australian wildlife care and rescue organisations, such as Wildcare Australia, Orphan Native Animal Rear and Release Association Incorporated, Wildlife Carers Darling Downs, Bat Care, Bat Rescue, Tweed Valley Wildlife Carers, and WIRES when reported as injured, sick, orphaned or abandoned. A very high proportion of adult flying fox injuries are caused by entanglement in barbed wire fences or loose, improperly erected fruit tree netting, both of which can result in very serious injuries and a slow, agonizing death for the animal if not rescued quickly.

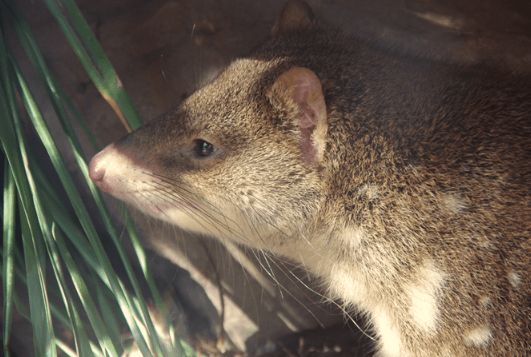

Quolls

Unfortunately for the beautiful quolls they are carnivorous which has led to them to come into direct conflict with humans. Their habit of stealing poultry in the past has made them direct enemies of poultry producers especially those in the organic poultry industry.

Quolls, Dasyrus maculata are much maligned. Rarely seen and very beautiful keeping foxes, feral cats, feral dogs, bandicoots and exotic vermon like rat numbers down, so why can’t we let them be. – andi Mellis

One species has been listed as threatened and one as has not nevertheless the specie are exposed to several threats, including loss of foraging habitats and suitable habitats for dens. When present in rural or urban environments, quolls are perceived more as a nuisance value as public opinion changes. They have suffered from direct killing by shooting, trapping and poisoning in the past. Baiting for wild dogs has been severely disrupted now with the protection of quolls in mind as they too will take wild dog baits.

Urbanization along the eastern seaboard of Australia has increased the potential for conflict between humans and quolls forcing the quolls to move further away and into limited suitable environments or environments too small and fragmented to support healthy populations.

Quolls living beside urban populations can be discouraged with tethered dogs at night and small electric fences which have proven very effective around poultry farms. Poultry sheds and runs, which need to be totally vermin proof to discourage the animals and cooked poultry carcases either disposed of properly or placed away from sheds so the quolls learn to forage away from the birds. This is particularly needed around ducks which are more likely to go off the lay once disturbed or haunted.

Bandicoots

Urbanization along the eastern seaboard of Australia has increased the dramatically the conflict between humans and bandicoots. Both the inner suburbs near parks, woodlands and watercourses and the outer suburbs of cities and towns are home to bandicoots. There are 7 species of which the southern brown Isoodon obesulus, the northern brown Isoodon macrousus and the long nosed bandicoot Perameles nasuta are the most commonly seen.

It’s difficult not to fall in love with a bandicoot, once you have encountered one scurrying, bounding around in the wild, despite their annoying digging of holes in search of grubs, beetles, worms and fungi. –

Great photo Annette Ruzicka.

All bandicoots are known to enter the yards of home owners causing a disturbance to lawns newly planted trees and shrubs. Bandicoots usually meet fatal interactions with domestic cats and dogs with their irate owners and neighbours continuing verbal abuse because of the damage and barking dogs if the animals do escape.

The main reason Bandicoots venture into gardens is because they are an excellent and easy source of fresh grubs and worms. This makes it a double edged sword.

If you are a conventional gardener using chemicals then there are likely to be more destructive grubs and pests that need removing so enter pest removalists Mr. Bandicoot with Mrs. Appetite. Shortly after dark they will quietly take up their positions and start their cleansing operations, ridding the garden of such pests. Instead of being applauded for a job well done we often grizzle of their after dinner habits of not cleaning the site up by levelling things off. Really is it that bad?

If you are a chemical free gardener using organic methods you have yourself to blame. You are encouraging all those wonderful worms and healthy bugs like centipedes, native slugs and snails into the garden which are readily feasted on by health conscience Bandicoots. After all who can blame them for wanting a delicious fat organically grown worm or fresh Escargot natural. Ah my mouth waters at the thought.

Understanding the driving factors behind the public’s perception of bandicoots will enable wildlife managers to develop effective and socially acceptable conservation strategies.

To understand the animals habits better six hundred and thirty questionnaires were distributed to the residents bordering Ku-ring-gai Chase and Garigal National Park in Sydney’s north east, to assess the sources of conflict. Eighty-three percent of respondents had experienced bandicoot interactions and 27mm had experienced interactions on a daily basis. The interactions with bandicoots influenced the respondents’ perception of a bandicoot as a nuisance or a pest. More surprising was the age of the resident and pet ownership status also influenced respondents’ attitudes. Contrary to anecdotal reports, there was an overall positive response from the community. The information gained from this survey will inform the development of community based management strategies for the bandicoots of northern Sydney and hopefully elsewhere in Australia where the animals are common.

In the mean time rodent proof fencing is the best method of deterring the animals. As Bandicoots are terrified of heights even a meter sends them into panic a low perimeter electric fencing should deter them as they will not attempt to climb or jump over such obstacles.

In conclusion the better sharing of income from tourism with the various ecosystems needs to be addressed. Wildlife is a strong generator of income through tourism and is worth over $8 billion dollars a year in Queensland alone and employs approximately 240,000 people directly and indirectly. It is the third biggest employer behind Farming, and retail and is significant sources of national revenue generation.

The tourism industry can increase employment within local communities by creating additional job opportunities as it expands. This approach would help compensate the cost of maintaining wildlife and contribute to changing local people’s negative perceptions of conservation.

I have displayed that even in Australia Human Wildlife Conflict exists and is escalating. I have attempted to illustrates that it is a worldwide issue and not an isolated Australia issue that needs urgent attention. In Asia there are problems with the Asian Elephants destroying agricultural fields and Pandas eating the bamboo that feeds her people. In China the government supports people where damage has been caused by endangered animals by paying the farmers for their lost crops. In Africa numerous carnivores kill cattle and monkeys threaten the food security of rural people but government initiatives are finding solutions and are reducing the impact in very few areas. In Europe and North America wolves and bears taking livestock and damaging property are being relocated to help restrict the conflict.

The real issue that is not being addressed quickly enough is the conflict which is being created by geographical regions or climatic conditions which is common to all areas where wildlife and human populations overlap. Coexisting and sharing the limited resources is essential for everyone’s well being.

Some of the management practices that are being applied under variable sometimes hostile environments, demographic, economic and social circumstances. It highlighted the costs, benefits and constraints of each option and tried to clarify which techniques could be best implemented under specific field conditions.

The overall picture; as explained in the introduction is very multifaceted. Some are unsustainable while others have huge physical barriers like country borders and even in Australia state borders can become huge disagreements mainly on political grounds and not environmental or scientific grounds. Others need to be heavily subsidized, financial or compensated while others are very costly and complicated devices to use which will not be affordable to most individuals in disadvantaged rural communities.

On the other hand, the review of the case studies above demonstrated that the conflict can be reduced through good management practices without resorting to wild culling, traditional husbandry techniques using dogs as well as low technology tools, based on local experience and low cost approaches. Obviously, some of these practices are only effective with some animal species and need to be combined with other methods or need refinement to adapt to the different topographies or species.

There is also a need to bring to light and disseminate innovative practices such as electric fencing, insurance programmes, compensation systems, natural resources and CBNRMS that have proven practical and cost effective in the field.

There is no single solution to every conflict and every preventative and mitigative strategy should be empirically tested for its cost effectiveness and possible impact on the ecosystem equilibrium before adoption.

The best scenario would imply integrated community development and wildlife conservation promoted by National Park Managers and supported by local populations. Community based conservation should give indigenous people the right to limited and sustainable use of natural resources while promoting tolerance towards wildlife, responsible interaction with their natural surroundings.

I believe that Human Wildlife Conflicts in the environment will continue until one or the other becomes extinct. The ultimate result and direction will ultimately depend on the decisions we make in preserving the system and restoring as much as we possibly can back to its original form without delay.

Further Comments from Members:

“Hi reader, it seems you use The Bible of Botany a lot. That’s great as we have great pleasure in bringing it to you! It’s a little awkward for us to ask, but our first aim is to purchase land approximately 1,600 hectares to link several parcels of N.P. into one at The Pinnacles NSW Australia, but we need your help. We’re not salespeople. We’re amateur botanists who have dedicated over 30 years to saving the environment in a practical way. We depend on donations to reach our goal. If you donate just $5, the price of your coffee this Sunday, We can help to keep the planet alive in a real way and continue to bring you regular updates and features on Australian plants all in one Botanical Bible. Any support is greatly appreciated. Thank you.”

In the spirit of reconciliation we acknowledge the Bundjalung, Gumbaynggirr and Yaegl and all aboriginal nations throughout Australia and their connections to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to their Elders past, present and future for the pleasures we have gained.