Cupaniopsis anacarioides is a good medium to large size tree that copes exceptionally well in drought, dry periods as well as in heat waves along the east coast.

Flindersia xanthoxyla showing a straight, non fibrous bole.

Carpobrotus virescens – Native Pig face with excellent fleshy leaves with non volatile oils as a ground cover.

Einadia hastata depicting fleshy leaves with a saline content.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxFire Retardant Plants

Fire researchers and climatologist researchers have predicted fires will become more severe, more frequent, and more widespread as a result of climate change especially during periods of La Nina and El nino.

Between 2020 and 2022, the Australia as did the rest of the world experienced triple La Nina episodes in a row, which stopped global temperatures from increasing as much as they otherwise would have as a result of human-caused climate change. Despite this very rare “triple dip” La Nina, the EU’s climate monitoring service stated that 2022 was the fifth warmest year on record.

Scientists warn that a return to El Nino conditions, on top of climate change, makes it almost certain that a new global temperature records will be set during the next five years.

There needs to be a lot more research on how Fire Retardant Plant Species, (FRPS or FRS) can be used to quell fires in the early stages and once the fire has taken hold. I do not claim to have all the answers and I am not privileged to have all the available information in my procession.

What is meant when people say Fire Retardant Plants?

Can plants really protect your property, your home or your outbuildings from fire?

The answer to both questions is complex and are as varied as there are plants. There are many characteristics which can determine whether a plant is more resistant to a fire. Looking at the first question the analyses of the individual’s characteristics will determine just how well a plant can cope with fire. Some of those characteristics will include:

Thick fleshy leaves,

Low growing dense foliage,

Foliage parallel to the ground,

Foliage does not contain volatile oils,

Plants that cope better in droughts or periods of dry weather,

Plants that cope well in extreme heat conditions,

Leaves that contain salt, and

The ability to suppress strong winds.

Added to the above the old adage when buying real estate also applies here, “Position Position Position” is extremely important when designing a fire retardant garden.

There is a lot, the home owner can do to help their plants become better Fire Retardant species. The use of a FRS planted amongst fire tinder plants on an uphill slope will do little to protect the property on the upside, whereas that same plant grown amongst other FRS with swales, the elimination of a middle tier and the use of size to deflect wind will enhance the properties security immeasurably.

Plants should be grown to help protect infrastructure, and should be selected as much for their beauty notating the many characteristics above, which will enhance the affects, so that a properties chances in a fire are diminished. The right plants planted in the right locations will have a remarkable ability in protecting property. In the 2019/20 wild fires; some homes were not burnt in in our area, which were surrounded by plants. Our local Brigade captain told me at a street meeting recently, in which I espoused the use of fire retardant plants that “The only home north of Ewingar that did not burn should have been the one that burnt to the ground.” She admitted that the house was surrounded by trees and had “Agapanthus lilies” to 5 meters around the family home. This is one of many examples where fire retardant plants may have had a very positive, profound effect. The exotic Agapanthus sp. could have been exchanged for the Native Crinum pedunculatum or Alocasia brisbanensis. This home obviously had more than just the plants planted immediately surrounding the home as the chicken coop and other out buildings also escaped damage. Luck or ingenious plant planning?

For tens of thousands of years bush fires; from lightning strikes, have landscaped the Australian bush. The flora and fauna best suited to these fires, survived and flourished, while others retreated in rainforests and transitional zones. Fire is inevitable and has a role in regeneration of many plants. 90% are started by people either accidently or deliberately. These fires were generally cooler burns and occurred at less frequent periods often several decades apart. “Lower stature Eucalyptus forests have typical fire intervals between 10 and 30 years, with other cases ranging between 20 and 100 years not the every year back burns that are often seen practiced recently.” Many Australian plants and animals have adapted to these infrequent cool burns as part of their life cycle. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-27225-4

In recent years human developments in bushland areas have increased the risk of bush fires not mitigated the chances. Landowners can significantly diminish the impact of bush fires by understanding how fires react in their environment, what plants burn freely and what plants help retard a fires progress. Reducing the impact levels that cause fires to crown, reduce the speed of the fires, the heat radiated from the fires and to an extent change the type of fuel available to the fires. Forests that historically burned every 75 to 150 years in some ecosystems have experienced up to four fires in just 25 years and the number of extreme bushfires, defined by the heat energy they release, has more than doubled between 2003 and 2023.

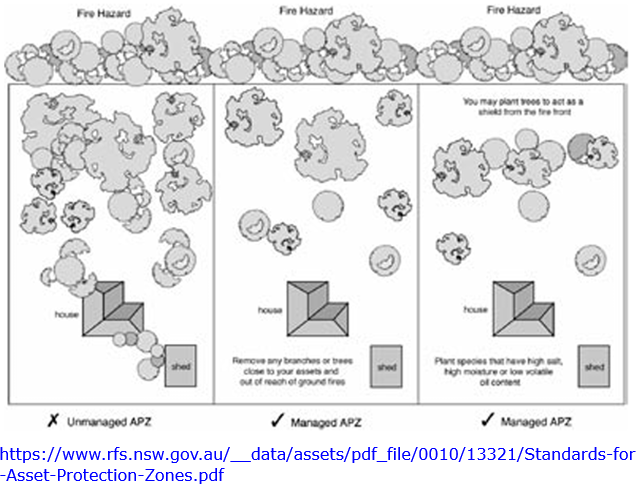

The Rural Fire Service highly recommends the creation and maintenance of an “Asset Protection Zone” or APZ. A well located and maintained APZ should be used in conjunction with other preparations such as good property maintenance, appropriate building materials and developing a family action plan if a fire is encountered. WHAT IS AN ASSET PROTECTION ZONE? An Asset Protection Zone (APZ) is a fuel reduced area surrounding your home or out buildings.

An APZ provides:

* a buffer zone between the natural bush and a structure on the property;

* an area of reduced bush fire fuel that allows better fire suppression;

* an area from which control burning may be conducted in an emergency in a safer manner. Control burns often create more fire prone weeds over a period of time which are more susceptible to increasing the intensity of future fires; and

* an area which allows emergency services access and provides a relatively safe area for firefighters and home owners to defend their property. Potential bush fire fuels should be minimized within an APZ.

The area surrounding our home was cleared 20 meters around the home by law at the time. Now that stands at 30 meters. It is this area and merging into the native bush that we created our FRS zone.

The vegetation within the planned zone should not provide a path for the transfer of fire to the asset either from the ground level or through the tree canopy.

Note the ground level is free of grass and debris, the middle tier is void while the bark on trees is solid not flaky or fibrous. The ground is in permanent shade and has a light covering of mulch which retains moisture. Trees are spaced to help eliminate competition for moisture and to break up wind flow. Here the temperatures recorded during February were up to 35 degrees Celsius cooler than ground temperatures 50 meters away in an exposed grassed paddock.

How fire retardant plants work:

There are several reasons that fires present which have to be taken into consideration when preparing your property to make it safer.

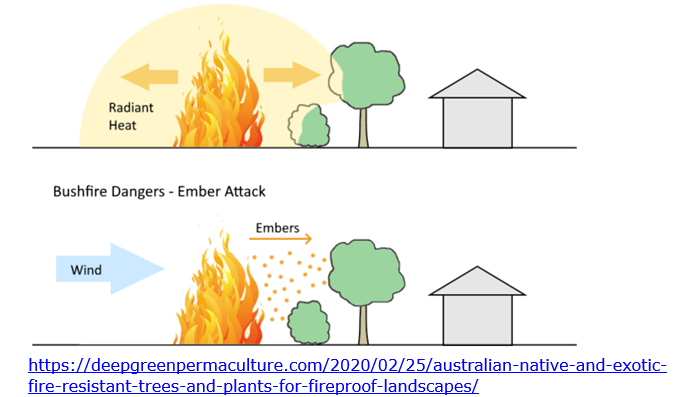

Radiant heat is the heat you feel when standing near a fire. Radiant heat is the biggest killer in fires, and the best protection from radiant heat is distance and barriers. Clear felling and the leaving of non FRPS in this area actually increases the radiant heat from fires as there is no natural barrier between the fire and the dwellings to deflect this radiant heat. Note the differences where buildings are surrounded by trees or in the open. Temperatures vary much more in the exposed positions.

Ember attack is the most common method where out buildings and structures are engulfed in fire. During bushfires especially wild fires, burning twigs, leaves and pieces of debris that can be carried by the wind across the land on or around structures, especially into gutters filled with leaves, so keep your gutters free of debris. Again clear felling in this area actually increases the number of embers which can come in contact with the ground, home and outbuildings increasing the chances of loss. FRPS are known to collect embers preventing them from starting spot fires in advance of the main fire.

Speed of a fire is enhanced mainly by topography, temperatures and wind. Fires create their own wind and the hotter the fire the greater the chance of fire storms or internal winds developing. Fires will always travel up slopes faster than down slopes. FRPS correctly positioned and the correct use of swales cannot be overemphasized to help reduce a fires attack.

Wind shear and eddies play a huge role in fires, especially along fire breaks and adjacent to forests where the land is cleared. Fires travelling parallel to a fire break will use the cleared section, usually containing dried grasses and annuals as a wind tunnel. The Eddies created often see speeds, which are much greater than the prevailing wind at the time. By planting a strong wall like row of trees will actually enhance shear and eddies.

Below is a typical wind eddy where the wind blows across the top of the trees then suddenly eddies around the cleared zone. At this point the fire can pick up more embers before dropping them further afield. This was a common occurrence in the 2019 bush fires where the fire gained speed and acted erratically across flat and gentle sloping grassy fields. Undulation on cleared grasslands create perfect eddies.

Trees will naturally break at wind speeds of 24m/sec or 152 kilometers/hour. This is always a risk along firebreaks and where there is a sudden or abrupt cessation of trees. I have adopted the centre model below around our home using Fire retardant trees and ground covers. There is a lack of shrubs in this area which helps to eliminate the chances of crown fires. Further out (in the fire hazard zone) I have adopted an area where a transitional zone occurs in the forest using fire retardant trees and ground covers. To ensure that good maintenance is carried out I have planted mainly native fruit trees and shrubs like Antidesma erostre, Dendrocnide excelsa (Stinging Tree) and Glycosmis trifoliate to mention a few. The barrier along the road front I have employed the use of many different species of Brachychiton and transitional zone trees like Araucaria bidwillii, Flindersia xanthoxyla and Micromelum minutum with ground covers like Myoporum boninense, Goodenia grandiflora and various species of Hibbertia like Hibbertia diffusa and Hibbertia riparia. The use of swales has an important function to reduce water flow and to create moist spots even during the worst droughts. This also utilizes water from off the road allowing the FRPS to grow under more favorable conditions.

A well planted area with FRS and areas of natural bush will take many years to come to fruition where the above qualities are fully realized. Our managed area has taken 15 years to develop, while the surrounding bushland is still undergoing change where the understory plants are slowly dissipating leaving the taller trees as the dominant feature. This area could take 40 or more years as we saw on our orchard at Nan Glen, which had not seen a fire, clearing of disturbance for 65 years.

Fuel types and Fuel loads Trends are strongly effected by climate change, human activity and time since the last disturbance, all contribute in determining fire risk of a given locality. In Australia controlled burns altar the natural frequency and type of fuel available to fires. There is much debate on the use of controlled back burns as a value to reduce fire risk, particularly during extreme fire weather conditions. Fuel types change over time with multiple frequent burning increasing more fire prone vegetation, highly volatile grasses like whiskey grass, Andropogon virginicus of annuals and short lived perennials over fire retardant longer lived perennials. Fire loads have a tendency to increase with subsequent burns and their distribution and structure are key determinants of fire spread, intensity and severity.

“….It is very likely that fuel management had no effect on the observed multi-decadal increasing trend in the burned area of forest fires. We also note that the main objective of fuel management is to reduce fire risk and severity, which might or might not result in reduced total burned area.” Morgan, G. W. et al. Prescribed burning in south-eastern Australia: history and future directions.  Aust. 83, 428 (2020).

Many grasses have fine vertical leaves, which under stress become infernos, whereas heavier chunky mulches that keep the soil temperatures cooler and help retain moisture by not allowing evaporation are used extensively. Look at burning a match by holding it upside down and then horizontally. Which burns the quickest? Mulches often retain more moisture, whereas weeds utilize whatever soil moisture is available. Mulches help create moist, cool microclimates. That’s why horizontal mulches are far better than a grassed or barren areas, which dry out very quickly on the onset of hot dry weather.

Shade is another extremely important aspect of temperature control and fire behavior. The cooler an area the lower the fire risk or at least the slower the burn and less intensity of the radiant heat which leads to less ember attack. The Syzygium australe, Flindersia schottiana and Cupaniopsis anachariodes are in our APZ area for this very reason. Even here there is a strong contrast in temperature differences.

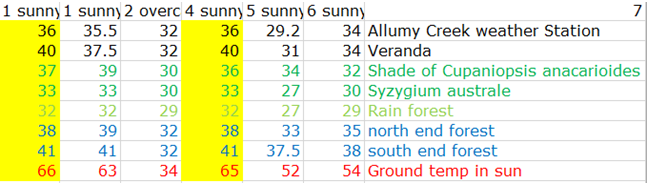

Some of the typical temperatures I took during the month of February/March (02.02.2023 to 06.03.2023) are as follows:

Despite the external temperatures varying greatly (31 to 40 degrees) the areas below the fire retardant trees remained fairly consistent (27 to 33 degrees) in the rain forest and beneath the Syzygium australe. The S. australe is the center of our APZ.

The ground temperature were taken 20 meters to the south of the Cupaniopsis anachariodes in an open grassy paddock in the full sun partial shade of the long grass.

The veranda was actually in the colour bond garage/computer room.

North end and south end were areas where natural Eucalyptus forests occurred.

Fire retardant trees systematically spaced will reduce wind speed near a building and also trap embers and sparks carried by the wind.

Fire retardant ground covers are able to catch burning embers without catching fire themselves, halt the embers from reaching the ground and also slow the travel of a fire through debris and litter on the ground.

Fuels can be controlled by:

1. Raking or manual removal of fine fuels. Ground fuels such as fallen leaves, twigs (less than 6 mm in diameter) and bark should be removed on a regular basis and mulched. This is fuel that burns quickly and increases the intensity of a fire.

2. Mowing or grazing of grass. Grass needs to be kept short and, where possible, well-watered so that it remains green and lush. This is difficult or even impossible during drought or during heat wave conditions.

3. Removal or pruning of trees and understory. The control of existing vegetation involves both selective fuel reduction (removal, thinning and pruning) and the retention of vegetation. Prune or remove trees so that you do not have a continuous tree canopy leading from the hazard to the asset. Separate tree crowns by two to five meters or have the crowns at different levels when mature. A canopy should not overhang within two to five meters of a dwelling. Native trees and shrubs; that are FRS, should be retained as clumps or islands and should maintain a covering of around 60mm of the area.

When choosing plants for removal, the following rules need to be adhered to:

1. Remove noxious and environmental weeds first. A list of noxious weeds can be obtained from your local council or at www.agric.nsw.gov.au/ noxweed/;

2. Remove more flammable species such as plants that have rough, flaky or stringy bark. Be aware of trees that have decorticating barks as these need cleaning on an annual basis. Some like Corymbia curtisii have a smooth bark but need to be cleaned annually after decortication is finished;

3. Remove or thin understory plants, saplings and shrubs 1 meter to three meters in height. This will happen naturally over time but is best hasten for top protection. The removal of significant native species should be avoided.

4. Contouring with the use of swales. Swales will slow water movement across the land and allows for deeper penetration of water. Swales also allow for a greater variation of better fire retardant plants. We employed paving bricks (over 250 meters) lined with large rocks contoured to slow water movement and increase water penetration.

Erosion must be considered when ploughing or using consistent high maintenance slashing particularly along fire breaks

The use of hard surfaces driveways, paths – Other protective features You can also take advantage of existing or proposed protective features such as fire trails, gravel paths, rows of trees, dams, creeks, swimming pools, tennis courts and vegetable gardens as part of the property”s APZ.

PLANTS FOR BUSH FIRE PRONE GARDENS: When designing your garden it is important to consider the type of plant species you like and their retardant characteristics as well as their placement and arrangement. Given the right conditions, all plants will burn. However, some plants are far less flammable than others.

Avoid:

- Trees with loose, fibrous or stringy bark;

Leptospermum trinervum has a beautiful bark but is a fire hazard. We maintained a few pockets further out, as it was the main tree for nesting Yellow Breasted Robins, Eopsaltria griseogularis.

2. Trees with fine foliage and

3. Foliage’s with an oil content. These trees and shrubs can easily ignite and encourage the ground fire to spread up to, and then through, the crown of the trees.

Consider:

- Trees and ground covers that have thick leathery or fleshy leaves.

- Trees, small shrubs or ground covers with a high salt content.

- Smooth barks without “ribbons” hanging from branches or trunks.

Typical growth habit of Cupaniopsis anachariodes above with thick smooth fleshy leaves, a dense canopy for reflecting radiated heat and trapping embers and a good fire retardant thick, smooth trunk below.

4. Dense crown and elevated branches.

5. Deciduous trees have a great advantage when they have no or few leaves. Most Australian native deciduous trees are leafless at the end of the dry season. Eg. Brachychiton rupestre or Brachychiton acerifolius.

For further information on appropriate plant species for your local council area contact the local “Australian Native Plant Society”. As a general rule, plant trees at the same distance away from the asset as their maximum height. When creating a windbreak, do not forget that the object is to slow the wind, redirect the wind and to catch embers with the plants selected rather than trying to block the wind.

Another approach is the 10/50 vegetation clearing.

If you live in an area close to the bush, you need to prepare your home. The 10/50 Vegetation Clearing Scheme gives people living near the bush an additional way of being better prepared for bush fires.

The scheme allows people in a designated area to:

Clear trees on their property within 10 metres of a home, without seeking approval; and

Clear underlying vegetation such as shrubs (but not clear trees if they are FRS) on your property within 50 metres of a home, without seeking approval.

You can find out if your property is in a 10/50 Vegetation by contacting your local council.

Image showing the clearing of trees within 10 metres of a home and vegetation within 50 metres of a home.

Important changes to the 10/50 scheme

Further changes have been announced to the 10/50 Vegetation Clearing Scheme. Legislative changes came into effect on 28 August 2015 and the 10/50 Vegetation Clearing Code of Practice has now been amended and takes effect commencing 4 September 2015.

You must now consider how the following changes affect your clearing proposal:

The definition of a tree has been amended to include multi-stemmed trees. This means you can no longer remove multi-stemmed trees beyond 10 metres.

The distance at which a tree may be removed has been clarified. You may only remove a tree if any part of the trunk that measures more than 30 centimetres in circumference (around the trunk) at a height of 1.3 metres above the ground, is within 10 metres of the external wall of the building.

If you are using the distance from a building on your neighbours land to use the 10/50 entitlement (and your buildings are not within 10 metres or 50 metres respectively), you must receive their written consent. Where the tree or vegetation is within 10 metres or 50 metres respectively of buildings on more than one adjoining parcel of land, you must receive written consent from each landowner who adjoins your land.

Clearing adjacent to farm sheds is now permitted under the 10/50 scheme.

A range of other changes to the 10/50 scheme are now in place in accordance with the commencement of the amended 10/50 Vegetation Clearing Code of Practice. Please review the amended Code of Practice and FAQs below in relation to your proposed clearing.

Changes to areas covered by the rule

The 10/50 Vegetation Clearing Scheme was introduced following the devastating 2013 bush fires in which more than 200 properties were destroyed.

The NSW Rural Fire Service (NSW RFS), in partnership with the Department of Planning and Environment and the Office of Environment and Heritage, undertook a formal review of the 10/50 Vegetation Clearing Scheme. It is clear from some submissions and feedback that while the scheme is designed to reduce bush fire risk, there has been some abuse of the fuel reduction provisions for other purposes.

As a result of the review of the 10/50 scheme, the entitlement area has been amended. The reduced entitlement area of 100m from higher risk vegetation has been maintained, covering 85 per cent of properties historically destroyed in a bush fire.

The easiest way to work out if you’re covered by the eligible area is checking the online tool. The tool contains the latest information on areas covered by the rule.

We carried out extensive temperature measurements during the early months of 2023 and are convinced that trees and ground covers with thick fleshy leaves and no oil content, have a decisive cooling factor on the area below the plants and in the vicinity where shade occurs. On our property Syzygium australe, Cupaniopsis anacharioides, several species of Plectranthus sp. now included in Coleus genus and a well established rainforest garden of several species of palms like Archontophoenix cunninghamiana, Livistona decora, Livistona australis, ferns Asplenium australis, Microsorum punctatum, mature trees like Alphitonia excelsa, Elaeocarpus reticulatus and Glochidion ferdinandi etc. On the hottest days the ground temperature was up to 70 degrees, yet 50 meters away beneath the rain forest and 30 meters to Syzygium australe the temperature was up to 45 degrees cooler. The average temperature difference on sunny days was 19.7 degrees cooler. In a shaded area in the dry schlerophyll forest just 40 meters away the temperature was 5 degrees warmer than in the shade of the Syzygium australe, Cupaniopsis anacharioides and beneath the various species of Coleus. The rainforest had very similar readings to the Syzygium australe.

It is best to eliminate shrubs or middle tier plants in the immediate vicinity of dwellings to help reduce crown fires. Fire Retardant Plants. It is important to use fire retardant plants native to your area even down to using local gene pool material if available. While the list below is relatively long choose plants carefully.

Plants that will resist a fire’s first wave in a bushfire, and still hold up strongly on the second wave if it occurs are as follows:

Botanical name  – Common name      Â

Acmena smithii – Lillypilly

Asplenium australis – Birds Nest Fern

Asplenium nidus – Birds Nest Fern

Atriplex cinerea – Coast Saltbush

Atriplex leptocarpa – Slender-fruit Saltbush

Atriplex limbata – Spreading Saltbush

Atriplex lindleyi – Flat-top Saltbush

Atriplex nummularia – Old-man Saltbush    Â

Atriplex rhagodioides – Silver Saltbush  Â

Atriplex semibaccata – Berry Saltbush

Atriplex vesicaria – Bladder Saltbush    Â

Bambusa arnemica – Large Clumping Bamboo

Carpobrotus glaucescens – Coastal Pigface

Carpobrotus modestus – Inland Pigface Â

Carpobrotus rossii – Karkalla Â

Carpobrotus virescens – Pigface

Chenopodium desertorum – Frosted Goosefoot   Â

Crinum pedunculatum – Native Lily

Cupaniopsis anacharioides – Tuckeroo

Dissocarpus biflorus

Disphyma crassifolium ssp. – clavellatum - Rounded, Noon-flower

Einadia hastata – Saloop   Â

Einadia nutans ssp. nutans – Nodding Saltbush    Â

Enchylaena tomentosa – Ruby Saltbush Â

Eremophila debilis – Creeping Emu-bush Â

Flindersia australis

Flindersia xanthoxyla

Goodenia grandiflora

Hakea salicifolia – Willow-leaved hakea

Maireana brevifolia – Short-leaf Bluebush Â

Maireana decalvans – Black Cotton-bush    Â

Maireana enchylaenoides – Wingless Bluebush   Â

Maireana erioclada – Rosy BluebushÂ

Maireana excavata – Bottle Bluebush

Maireana georgei – Slit-wing Bluebush  Â

Maireana microphylla – Small-leaf Bluebush

Maireana oppositifolia – Heathy Bluebush

Maireana pentagona – Hairy Bluebush

Maireana pentatropis – Erect Bluebush

Maireana pyramidata – Sago Bush

Maireana radiata – Radiant Bluebush

Maireana rohrlachii – Rohrlach?s Bluebush

Maireana sedifolia – Pearl Bluebush

Maireana turbinata – Satiny Bluebush

Melia azedarach – White Cedar

Mimulus repens – Creeping Monkey-flower

Myoporum boninense – Coastal Boobialla

Myoporum insulare – Common Boobialla

Myoporum parvifolium – Creeping Myoporum

Myoporum petiolatum

Rhagodia candolleana – Seaberry Saltbush

Rhagodia crassifolia – Fleshy Saltbush

Rhagodia parabolica – Fragrant Saltbush

Rhagodia spinescens – Hedge Saltbush

Sarcocornia quinqueflora – Bead Weed (Has great potential as a food vegetable in Chinese like dishes)

Sarcozona praecox – Sarcozona

Scaevola aemula – Blue Fan-Flower

Scaevola calendulacea – Dune Fan-flower

Scaevola hookeri – Creeping Fan-flower

Shoenoplectus mucronatus

Sclerolaena diacantha – Grey Copperburr

Sclerolaena spp. – All Copperburrs

Selliera radicans – Shiny Swamp-mat

Sesuvium portulacastrum

Syzigium australe – Lilly Pilly

Syzigium leuhmanii – Lilly Pilly

Syzigium oleosum – Lilly Pilly

Tecticornia spp. all – edible with a taste reminiscent of asparagus & forget the salt

Tecticornia australasica

Tecticornia halocnemoides

Tecticornia indica

Tecticornia pergranulata

Zygophyllum apiculatum – Pointed Twin-leaf

Zygophyllum billardierei – Coast Twin-leaf

Zygophyllum spp. – All Twin-leaf plants

Fire Retardant Plants. Plants that will not burn in the first wave of a bushfire, but may burn once dried out in a second wave:

Botanical name Common name

Acacia acinacea – Gold-dust Wattle

Acacia argyrophylla – Silver Mulga    Â

Acacia baileyana – Cootamundra WattleÂ

Acacia binervia – Coast Myall

Acacia brachybotrya – Grey Mulga     Â

Acacia buxifolia – Box-leaf Wattle

Acacia caerulescens – Limestone Blue Wattle      Â

Acacia cardiophylla – Wyalong Wattle

Acacia complanata ? Flat stem wattle

Acacia cultriformis – Knife-leaf Wattle

Acacia Cyclops – Western Coastal Wattle

Acacia dealbata – Silver Wattle

Acacia deanei – Deane?s Wattle

Acacia decora – Western Silver Wattle      Â

Acacia decurrens – Early Black-wattle   Â

Acacia elata – Cedar Wattle  Â

Acacia farinosa – Mealy Wattle

Acacia fimbriata – Fringed Wattle

Acacia floribunda – White Sallow-wattle Â

Acacia glandulicarpa – Hairy-pod Wattle     Â

Acacia howittii – Sticky Wattle   Â

Acacia implexa – Lightwood

Acacia iteaphylla – Flinders Range Wattle

Acacia kettlewelliae – Buffalo Wattle Â

Acacia ligulata – Small Cooba   Â

Acacia mearnsii – Black Wattle

Acacia melanoxylon – Blackwood      Â

Acacia microcarpa – Manna Wattle  Â

Acacia nano-dealbata – Dwarf Silver Wattle

Acacia obliquinervia – Mountain Hickory Wattle   Â

Acacia oswaldii – Umbrella Wattle

Acacia pendula – Weeping Myall

Acacia penninervis – Hickory Wattle Â

Acacia podalyriifolia – Queensland Silver Wattle  Â

Acacia pravissima – Ovens Wattle  Â

Acacia prominens – Gosford or Golden Rain Wattle   Â

Acacia salicina – Willow Wattle  Â

Acacia saligna – Golden Wreathe Wattle            Â

Acacia stenophylla – Eumong Â

Acacia terminalis – Sunshine Wattle

Acacia vestita – Hairy Wattle

Acmena smithii

Ajuga australis – Austral Bugle

Alectryon oleifolius ssp canescens – Cattle Bush

Alyxia buxifolia – Sea Box

Angophora costata – Smooth-barked Apple

Avicennia marina subsp. australasica – Mangrove

Blechnum neohollandicum – Prickly Rasp-fern

Blechnum parrisiae – Common Rasp-fern

Brachychiton – all

Brachychiton acerifolius – Flame tree

Brachychiton australis

Brachychiton populneus – Kurrajong

Brachychiton rupestris – Bottle tree

Bursaria spinosa Sweet Bursaria

Cheilanthes austrotenuifolia – Green Rock-fern

Cheilanthes sieberi – Narrow Rock-fern

Cissus Antarctica

Coprosma hirtella – Rough Coprosma

Corymbia maculata – Spotted Gum

Corymbia henryi

Correa glabra – Rock correa

Curcuma australasica – Cape York Lily

Cyathea australis – Rough Tree-fern

Derwentia derwentiana – Derwent Speedwell

Dianella brevicaulis – Small-flower Flax-lily

Dianella callicarpa – Swamp Flax-lily

Dianalle caerulea – Paroo Lily

Dianella longifolia – Pale Flax-lily

Dianella revoluta – Black-anther Flax-lily

Dianella tarda – Late-flower Flax-lily

Dianella tasmanica – Tasman Flax-lily

Dichondra repens – Kidney-weed

Doryanthus excels – Giant Spear Lily

Doryanthus palmeri – Spear Lily

Eremophila deserti – Waterbush

Eremophila saligna – White Emu-bush

Eremophila santalina – Sandalwood Emu-bush

Ficus – all

Ficus macrophylla – Moreton Bay Fig

Ficus rubiginosa – Rusty Fig

Flindersia xanthoxyla

Frankenia pauciflora – Southern Sea-heath

Grevillea nudiflora – Leafless-flowered Grevillea

Hymenosporum flavum – Native Frangipani

Lagunaria patersoni – Lord Howe Island Hibiscus

Lasiopetalum macrophyllum – Shrubby Velvet-bush

Lasiopetalum schulzenii – Drooping Velvet-bush

Micromelum minutum

Myoporum acuminatum – Boobialla

Myoporum bateae – Pink Boobialla

Myoporum montanum – Waterbush

Myoporum petiolatum – Sticky Boobialla

Myoporum platycarpum – Sugarwood

Myoporum velutinum – Woolly Boobialla

Pandorea jasminoides – Native Jasminum

Pittosporum angustifolium – Weeping Pittosporum

Pittosporum bicolor – Banyalla

Pittosporum phylliraeoides – Butterbush

Pittosporum revolutum – Rough-fruit Pittosporum

Scleranthus biflorus – Twin-flower Knawel

Senecio odoratus – Scented Groundsel

Senecio pinnatifolius – Variable Groundsel

Solanum aviculare – Kangaroo Apple

Solanum esuriale  – Quena

Solanum laciniatum – Large Kangaroo Apple

Solanum simile – Oondoroo

Viola banksii – Ivy-leaf Violet

Viola hederacea – Ivy-leaf Violet

Further Comments from Readers:

Hi reader, it seems you use The Bible of Botany a lot. That’s great as we have great pleasure in bringing it to you! It’s a little awkward for us to ask, but our first aim is to purchase land approximately 1,600 hectares to link several parcels of N.P. into one at The Pinnacles NSW Australia, but we need your help. We’re not salespeople. We’re amateur botanists who have dedicated over 30 years to saving the environment in a practical way. We depend on donations to reach our goal. If you donate just $5, the price of your coffee this Sunday, We can help to keep the planet alive in a real way and continue to bring you regular updates and features on Australian plants all in one Botanical Bible. Any support is greatly appreciated. Thank you.

In the spirit of reconciliation we acknowledge the Bundjalung, Gumbaynggirr and Yaegl and all aboriginal nations throughout Australia and their connections to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to their Elders past, present and future for the pleasures we have gained.